The Work of Artists Is Not Play

When the public reads stories in the media about visual artists, it is all too often about art stars that are selling their works for six figure sums or an item detailing glamorous parties on the art fair circuit.

A shot of reality is being offered at the CUE Foundation under the leadership of Cevan Castle, a public programming fellow who has organized a six-part series of talks entitled, “If It’s Not work It Must Be Play.” I attended the first two panels, Economists on Under-Compensation of Labor in the Arts, and W.A.G.E.- How Creative Labor Should Be Compensated. The third, The Artists Financial Support Group Speaks Openly about Money and Debt, will be held on January 30. The following announced topic is Artists and Gentrification: Community Development Experts On Improving Neighborhood Stability.

As an introduction, Castle ran down a continuum of concerns for artists ranging from the nuts and bolts premise of, “What is the value of our labor?” to the imperative of moving toward “actionable ideas.” When I asked her about her motivation in tackling these themes she said,

“I wanted to look at current concerns and obstacles to art practice, particularly for our region. Although we live in one of the great art centers, the city is losing the characteristics that made it hospitable to art practice. There are large segments of the population that live in increasingly precarious circumstances. The predominant models in the art business are obviously unsustainable, as artists are repeatedly asked to personally subsidize public art consumption and the power figures in the art market. Under the pressures of real estate costs, educational costs, increase in costs of living and yet little to no pay, the urgency to revisit business models that work for artists grows. That is, if we truly believe that art contributes something significant, beyond it’s current role in speculative real estate development, to our society.”

Laying groundwork at the first session, four Feminist Labor Economists parsed material through what Dr. Deborah M. Figart called a “critical gaze.” This translated as examining data on premises other than solely earnings. Figart stated that the “creative class is an important part of the economy, but [traditional] economists overlook important factors.” These can encompass education, location, work time, marital status and children. Then there are the societal norms of “who is appropriate for a job and what it’s worth.” Ironically, when there are greater numbers of women and people of color in a specific field, the “pay goes down.”

Figart outlined the imbalance of power between artists and business people, and the wage gap between “bohemian and non-bohemian” workers. For creatives, income is often pieced together with part-time jobs. Salaries and job security are low, and it doesn’t help that there is an overlap between what is considered work and “leisure activity.” Figart underscored the “devaluation of work in the arts” except for the top 1 percent, adding, “and then there’s everyone else.”

Ellen Mutari spoke about the redefinition of work as going beyond the singular yardstick of “a paycheck.” In addition to work as financial security, she identifies it as “identity, purpose, and personal fulfillment.” She discussed the consumerist notion of “work as a commodity—something that you sell,” instead putting forth that work has “multiple dimensions.” Mutari pointed to the “false premise of the cultural narrative” which promotes the idea that artists don’t care about anything except “making the work and having it seen.” This concept, she suggested, “yields to underpayment in the arts.”

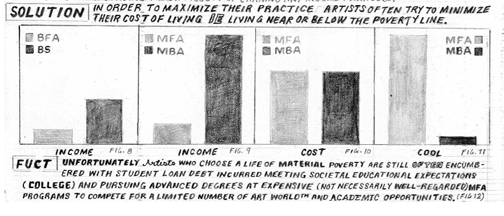

Can the system be changed? That was Catherine Mulder’s rhetorical question. She envisioned the goals of “eradicating exploitation” and pushing for artists to have job security and agency. A labor activist, Mulder spoke of the guilds during the Middle Ages, where members taught and trained future artisans. In today’s landscape, there is an output of MFA students “mired in debt.”

Mulder proposed creating new models for unions, to provide “undergirding” for creatives. She referenced the recent legal development in 2014 (the case of New York artist Susan Crile) that guaranteed artists that even if they didn’t “make a profit” from their art, that their business deductions would be honored—rather than dismissed as a hobby.

Mulder proposed creating new models for unions, to provide “undergirding” for creatives. She referenced the recent legal development in 2014 (the case of New York artist Susan Crile) that guaranteed artists that even if they didn’t “make a profit” from their art, that their business deductions would be honored—rather than dismissed as a hobby.

When questions were taken from the floor, the matter of artist royalties came up. Figart was quick to respond, “When you sell a work of art, there are no residuals.” She said dryly, “I have a problem with that.” The point was raised about the need to delineate art as “intellectual property.”

There was plenty of discussion about the “obscenity” of the auction houses and the 1 percent buyers who were establishing value for their connections. The feminist economic viewpoint is that “stuff that doesn’t make money isn’t valued.” Figart closed out the evening with the aphorism, “You have to think outside of the box to change the box.”

At the second gathering, concrete actions were examined. Lise Soskolne offered an outline of the efforts the New York based activist group W.A.G.E. are putting forth to build a “sustainable model for wage certification.” The group’s mission is based on a manifesto that was written in 2008. Soskolne was emphatic that art workers needed to be “remunerated in order to survive.” Before getting into the nitty-gritty of her talk, she noted with a touch of humor, “We demand compensation for making the world more interesting.”

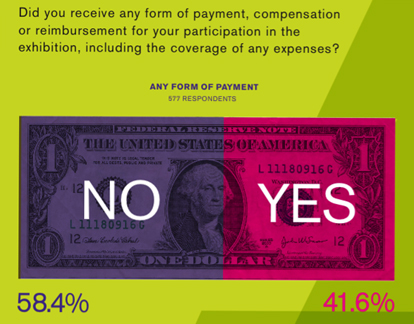

Drilling down on several of the basic conundrums that creatives repeatedly face, she delivered one of the top excuses for non-payment: “Exposure.” Soskolne asked, “When an artist is presenting content, why is there no pay?” W.A.G.E. took a survey in 2010 to dig into the reasons why artists were always broke. They targeted both visual and performing artists who had been involved with a museum or non-profit space during the time period of 2005-2010. The results weren’t pretty. Several well-known institutions were singled out by respondents for their behavior. Soskolne emphasized that foundations dispensing funds needed to hold non-profits accountable, applying “downward pressure.” I particularly liked the poster, with its visuals and anonymous comments from the questionnaire. Succinctly underscoring a key point was the observation, “Free means useless for society, and we’re not.”

Resolutions moving forward may need to be addressed through the courts. There was the mention of lawsuits under Title IX, as redress to gender inequity in the art world. Resale rights and artist royalties were deemed the “missing piece.” The example was given of The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement that was drawn up in 1971 by lawyer Robert Projansky and Seth Siegelaub, an art dealer and activist. The goal was to safeguard the rights of artists and their work. Hans Haacke is an artist who has consistently made use of the contract. Another agreement template, written in 2009 by feminist activist and artist Mary Beth Edelson, can be found on the W.A.G.E precedent page.

Soskolne said, “We’re trying to systemically change things.”

It may not happen overnight, but a transparent conversation is essential. Educating artists is a good place to start.

Photos: Courtesy of Wage for Work

Marcia, I’m glad you posted this article. All artists must get involved in this and ask to be paid every time they participate in any event related to their artwork.

Thanks for this Marcia, but I must comment..

Play has gotten a bad name lately, with our society’s emphasis on a kind of dismal utilitarianism, which values hard work and material success. But it is disappointing that you advise artists to distance themselves from something that is essential to all creative work, be it music, acting, or dance, or the fine arts. The value of play is under attack, but artists should stand up for the need to have playful pursuits in a healthy society, rather than giving in to the trend that labels play as something not worthy of payment – and has you telling people making art is not play. You would have had a hard time convincing Pete Seeger, who I won a Grammy for recording. Experts like Dr. Stuart Brown make some very compelling arguments for why society should esteem play more highly. And my essay “Recognizing the Value of Play,” where I argue it is essential even in hard-nosed subjects like Physics research, recently won an award.

People should get paid for creative pursuits like the fine arts. But to say that making art is not play demeans it. If it is not play, or does not at least feel like play sometimes, perhaps you are not doing it right. However, people should be paid to play, and the value of play should never be under-estimated.

All the Best,

Jonathan

Jonathan J. Dickau – This article is not EITHER/OR – play or compensation. Marcia Yerman is reporting a series of panels and not editorializing. As an artist it is much more complicated – when I work I don’t think about the remuneration – I am working out ideas and totally absorbed in the work – leaving one world to go into another.

Thanks Grace,

I liked the article, and I appreciate that she is reporting on the panel discussion by the CUE foundation, but the panel organizers made it either/or when it should never be framed that way. So the CUE folks are catering to the public perception with a catchy title that apes public opinion, but unfortunately exacerbates the problem.

The challenge remains to make playful activities cool again, and to acknowledge that creative folks deserve to get paid as much as those who are skilled workers in other areas. The problem is; Marcia’s choice for a title makes it look like she is OK with society’s emphasis on hard work and material success, so long as artists still get paid. I am not, and I think creative folks will only get a fair shake when play is given its proper value.

All the Best,

Jonathan