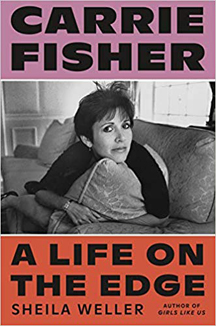

Carrie Fisher’s Turbulent Journey

Carrie Fisher: A Life on the Edge is author Sheila Weller’s newest addition to her body of work, which is often situated at the crossroads between women’s issues and cultural observation. In previous books, Weller examined several women through the prism of music and media. With her biography of Fisher, her subject is so outsized, it is the equivalent of a group portrait: The many facets of Carrie.

Carrie Fisher: A Life on the Edge is author Sheila Weller’s newest addition to her body of work, which is often situated at the crossroads between women’s issues and cultural observation. In previous books, Weller examined several women through the prism of music and media. With her biography of Fisher, her subject is so outsized, it is the equivalent of a group portrait: The many facets of Carrie.

Who was she? The child of a Hollywood couple; inhabitor of the career-defining role of Princess Leia in “Star Wars”; actress and writer; friend to innumerable celebrities; daughter, mother, wife (married to Paul Simon); partner.

Yet, perhaps the one aspect of Carrie that would impact and influence everything — was being the genetic inheritor of a predisposition to drug addiction and bipolar disorder (both from her father). These two elements would have a tremendous bearing on her entire existence.

As Leo Tolstoy observed, “Each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Carrie and her family lived out their dysfunction against the backdrop of screaming headlines splashed across tabloid newspapers. In 1959, her songster father, Eddie Fisher, dumped his MGM wholesome bride, Debbie Reynolds, for megastar and beauty, Elizabeth Taylor. The actions and lifestyles of actors and actresses were starting to be revealed in a vastly different way from the 1940s and 50s, when major studios were able to whitewash, spin, and cover up news that was detrimental to the image (and dollar value) of their stars.

Carrie would become part of the unraveling of 1950s American society (She was born in 1956.) when “Father Knew Best” and there was no alcoholism, drug use, homosexuality or decision-makers who weren’t white men. Rather, Carrie’s time would unfold against the backdrop of independent film, Woodstock, Vietnam, social upheaval, and the morphing roles of women.

It is true that Carrie navigated her ordeals within the confines of extreme privilege and Hollywood glamour, unlike the average person. Yet, the essence of her evolution and aspects of her struggles will be easily recognized to other women — especially of her generation. Her myriad insecurities, one of the continuous threads of her personal history, is what makes this telling of her life accessible to an audience beyond just her fans. Carrie perseverated about if she were pretty enough, smart enough, thin enough — and then as she aged…not young enough. It will ring an unwelcome bell.

Ultimately, after being attacked on Twitter for her appearance in “The Force Awakens” (2015), she was able to push back against the fat and age shamers. With her trademark incisiveness said acerbity, Carrie proclaimed, “Youth and beauty are not accomplishments. They’re the temporary, happy by-products of time or DNA.”

Carrie left high school at 15, and began her movie career two years later when she portrayed a Beverly Hills teenager in Warren Beatty’s “Shampoo.” Very few people are aware that she attended the prestigious Central School of Speech and Drama in London in 1974, before snagging the part of Princess Leia at 19. It was a role that would freeze her in time, like a specimen trapped in amber. There were benefits, but also plenty of liabilities. Some of her nuanced performances — in movies like “Hannah and her Sisters” and “When Harry Met Sally” — were overlooked. She also appeared very briefly on Broadway (when she was 26), replacing Amanda Plummer as the young nun in “Agnes of God.”

By her twenties, people were already recognizing Carrie’s rapier wit and originality. Simultaneously, Weller references those who spoke about her vulnerability and neediness. Carrie’s perpetual generosity to others, both monetary and emotional, was most probably part of her quest for love and approval — something she craved from both of her self-involved parents. Ironically, despite her own extensive litany of problems, she became a caretaker to both Debbie and Eddie as they grew older. With her mother, after years of competition and discord, they developed a co-dependent relationship (They had houses next door to each other.). With her father, who tapped her for money, made inappropriate remarks, and sometimes shared drugs with her, there remained an unfilled quest for a love that Carrie hoped would be realized.

When Carrie became a “writer who acted,” she moved into what would prove to be the most comfortable space for herself. Despite having a great singing voice, she wanted to completely differentiate herself from her parents. She penned numerous books, including “Postcards From the Edge” (It was made into a movie with Meryl Streep and Shirley MacLaine.), and was a sought after script doctor.

At the age of 24, Carrie was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. She rejected that conclusion by doctors, and the option of taking lithium to balance her moods. In 1985, she was again diagnosed — with bipolar two. She was finally able to accept the information, specifically as an explanation for her behavior and extreme emotional swings. However, as Weller points out, the way that Carrie went about dealing with her circumstances was “in Carrie style — with the unofficial caveat that she didn’t have to follow treatment in an orthodox fashion.”

Carrie made a point of being open about her bipolar status, to share her experiences and destigmatize the condition. In an interview with Diane Sawyer in 2000, she stated flatly, “I am mentally ill. I can say that.” The following year, she agreed to be the cover story for Psychology Today.

I spoke with Weller by phone to dig into Carrie’s legacy — specifically to other women.

“She had a big personality and a lot of honesty, about herself as well as others,” Weller told me. “Exaggerated emotion and intensity is more welcomed in men,” she said. Weller pointed to the example of actress Margot Kidder, who was “ridiculed,” and not treated with the same empathy as Robin Williams. “It’s harder for women to behave unconventionally,” she added.

Weller emphasized that even with Carrie’s “intense challenges, she remained productive.” That is evidenced in anecdotes about Carrie’s perpetual travels, performances, and writing.

“Carrie was a woman who was famous just for being herself,” pronounced Weller. “She broke boundaries. She understood that she had a disorder that didn’t have a cure. She used her honesty to help other women, and increasingly understood the importance of kindness.”

Weller’s biography illustrates the breadth and scope of Carrie’s difficult but full journey. She went through so much — from the emotional fallout of a famous and fractured family, to the procedure of electroconvulsive therapy [ECT] as a treatment. She always came out the other side…until she didn’t.

The book left me with feelings of sadness. But then I did something Carrie might have done. I rented “Postcards from the Edge” — and laughed along with her.