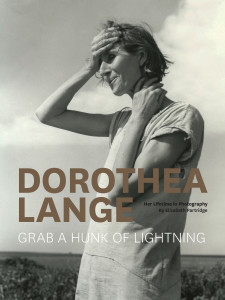

Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning

One of America’s foremost photographers, Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), has too often been viewed through the narrow prism of her best-known work. The groundbreaking photos that she took during the Great Depression of breadlines, and the despair she recorded of those forced to migrate in response to the Dust Bowl, are permanent fixtures in the pictorial history of the United States. However, the depth and range of her photography extend far beyond those iconic depictions.

One of America’s foremost photographers, Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), has too often been viewed through the narrow prism of her best-known work. The groundbreaking photos that she took during the Great Depression of breadlines, and the despair she recorded of those forced to migrate in response to the Dust Bowl, are permanent fixtures in the pictorial history of the United States. However, the depth and range of her photography extend far beyond those iconic depictions.

In the book, Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning, Lange’s “lifetime in photography” is presented with equal weight given to Lange’s intuitive eye for structure and composition, as well as to her burning commitment to social justice.

Author Elizabeth Partridge is uniquely positioned to deliver the 192-page monograph. The goddaughter of Lange and granddaughter of Imogen Cunningham, Partridge has captured the essence of Lange’s work and heart. With over one hundred photographs, Partridge traces the themes and world events that shaped Lange’s persona and oeuvre.

I spoke with Partridge to discuss her vision for the book and how she chose which prints would be included. She explained that she wanted to present the “narrative arc” of Lange’s output, and was extremely conscious of the “layout.” Lange regularly used the spoken words of her subjects paired with their photographs, and Partridge pulls from that precedent in the text she has chosen to feature.

In a discussion of Lange’s reticence to identify as “an artist,” Partridge emphasized that at the high point of “social ferment” in the nation, documentary photographers did not want to be considered fine artists. Partridge said, “That was considered a diminishment.”

It wasn’t until late in her life, when Lange was traveling with her second husband, Paul Taylor, that she truly connected to herself as an artist. Her thirty-year partnership with Taylor had originated in their shared experiences recording on the ground conditions around the country for the Farm Security Administration. When Lange voyaged overseas with Taylor, in his capacity as a land reform expert for the United Nations, she was free to operate as a photographer without an assignment. It was at this time Lange said, “I believe that I can see. That I can see straight and true and fast.”

In her essay, Partridge breaks down the periods of Lange’s life and career into sections: Childhood; Apprenticeship; The Trade; To the Streets; To the Fields and Camps; World Traveler. The culmination is the genesis of Lange’s one-person exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1966—which opened three months after Lange’s death. While organizing her photos, Lange pushed past ill health, arranging and rearranging prints on a wall as she culled from thousands of negatives. Lange had a vision of what she aimed to accomplish with the exhibit. Partridge quotes her saying, “The time for me is past to do what is called the ‘documentary’ thing. I have done that. But out of those materials, I want to extract the things that are the universality of the situation, not the circumstance.”

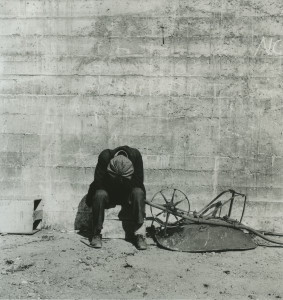

Like the MoMA exhibit, the book contextualizes Lange’s pictorial journey, but most importantly, allows the photos to stand as individual pieces. Even when an adjacent page has comments by Lange, as with Man Beside Wheelbarrow, it is still the visual components that make the portrait so visceral.

Man Beside Wheelbarrow

Man Beside Wheelbarrow

San Francisco, California, 1934

The man’s cap, reminiscent of the one worn by Henry Fonda in his portrayal of Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath, echoes the shape of the wheel. The creases in the hat mimic the spokes. The darkest area is the abstracted shape of the coat, which gives rise to pant legs that blend with the shadows. Making contact with the earth are scuffed and worn shoes, similar in tonalities to the body of the wheelbarrow. The pockmarked brick wall bears the white graffiti markings of some individual who needed to be heard. It could be a war-torn area rather than San Francisco in the late thirties.

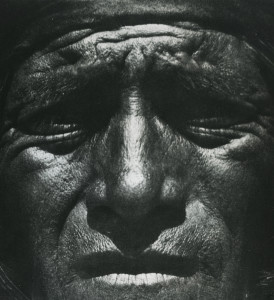

In the 1920s, Lange spent a period of time in the Southwest with her first husband, artist Maynard Dixon. Here she experienced the wide-open spaces and the majesty of nature. She photographed the Native Americans of the region. It was a precursor to her interest in the stories of those who had been oppressed, beaten down, or ostracized by mainstream culture.

Hopi Indian During Snake Dance

Hopi Indian During Snake Dance

Walpi, Arizona, 1926

Lange detailed the lives of black denizens in the south during the late 1930s. From North Carolina to Mississippi and Alabama, Lange observed moments from their daily routines. The pictures serve as archives of those who hoed the cotton, children of sharecroppers, and the hierarchy of power between the races, seen clearly on a country store’s porch. Ex-Slave with a Long Memory captures an elderly woman whose lifetime has straddled two eras. Her walking staff imbues her with a Biblical presence—a prophet with an oral history full of untold narratives.

Ex-Slave with a Long Memory

Ex-Slave with a Long Memory

Alabama, 1937

Type of Hay Derrick Characteristic of Oregon Landscape is a piece of documentation that works exquisitely as a study in line and composition. Although it records a farming tool, it could be a shot of an outdoor sculpture—each component interactive and balanced between the tensile strength of wood, chain and wire.

Type of Hay Derrick Characteristic of Oregon Landscape

Type of Hay Derrick Characteristic of Oregon Landscape

Irrigon, Morrow County, Oregon, 1939

During the 1950s, Lange tackled environmental issues in the series “Death of a Valley.” It was a prescient examination of the human impact upon the land. Witnessing a valley north of San Francisco being flooded to create a dam, Lange depicted the destruction of a habitat, as opposed to what at the time was seen as “progress.” Unlike the hay derrick, this piece of modern machinery looks like an iron monster with curved teeth poised to attack the earth. Lange renders an interplay of rhythms. Two types of mesh grating in the back, and the diagonal structures that comprise part of the tractor’s design, interact with the darkened wheel at the center of the photograph. Diminished by the massive equipment, is the young man operating it.

Bulldozer

Bulldozer

Berryessa, California, 1956

Perhaps the event that devastated and impacted Lange the most was the internment at the beginning of World War II (by Executive Order) of Japanese-American citizens. Tapped by the government, who knew her abilities from the Farm Security Administration, the War Relocation Authority wanted visual proof that the evacuation and prison camps were humane and warranted, a necessity for national security. Lange viewed the actions as impingements upon civil and human rights, and subverted her assignment with photographs that turned the government’s premise upside down. Lange demonstrated the shortcomings of America without flinching. She said, “The deeper I got into it, the bigger it became.” She chose her subjects with specificity: children with identification tags, conditions at Manzanar, and a shot of the American flag waving in the wind, framed by mountains, sky, and barracks. The subtext was clear. Much of Lange’s work was impounded and remained unavailable to the public until 2006. A simple visual of two items of clothing drying on a wash line captured it all. One has a traditional Japanese design; the other has gingham checks—as American as apple pie.

Wash-Day 40 Hours Before Evacuation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry

Wash-Day 40 Hours Before Evacuation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry

from this Farming Community

Santa Clara County, San Lorenzo, California, 1942

In Lange’s travels with Taylor, “field work” was no longer the motivation. However, whether Lange was taking pictures in Ireland, Korea, Vietnam, Ecuador or Egypt, the priority was always the people, their lives, and their struggles.

Having faced the challenges of functioning in a man’s world in the early 20th century, Lange’s camera was always attuned to the circumstances of women—and their station in life. Her representation of a woman in Pakistan from 1958 resonates as strongly today. It is both frightening and riveting to contemplate the life of the person beneath the article of clothing. The texture of the cotton, the design in the crown, the dark holes poked out for her eyes, the stitching mending a rip—they all add to the ghostlike appearance of an individual who has been instructed by her culture not to exist openly. Upon closer examination, an arm comes into view with a hand upraised in a supplicating pose. Rather than framing the figure centrally, Lange has placed her off to the side.

Lange contracted polio when she was seven. The illness left her with a withered foot and a limp. It also imbued her with a great sense of empathy towards others. The displaced, disenfranchised, and discarded—Lange gave them all a voice.

Lange’s search for truth yielded political and philosophical understanding, while remaining a timeless testament to the human spirit.

All photos: Courtesy of Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning

Published by Chronicle Books