“Blacklisted: An American Story” An Exhibit More Timely than Ever

Civil Rights Congress

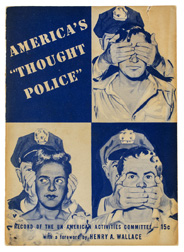

America’s “Thought Police”: Record of the UnAmerican Activities Committee, 1947

Courtesy of the Unger Family

The New York Historical‘s exhibition, “Black Listed: An American Story,” extended through November 2, is a presentation not easily forgotten. A traveling show originated by the Jewish Museum Milwaukee, previously mounted in Los Angeles, and expanded by The New York Historical, the lessons of the “Hollywood Red Scare” couldn’t be more relevant to the moment.

My interest in the Blacklist began in eighth grade when my social studies teacher screened “High Noon.” He explained that the film was not just a Western, but rather a portrayal of townspeople who lacked the courage to speak or act in opposition to threatening forces out of fear. He informed us that the writer, Carl Foreman, had been blacklisted

The exhibition is handsomely mounted, with placards that tell the story in vibrant graphics of black, white, grey, and red. There are over 150 objects on display, including pamphlets, personal items from the families of those targeted, letters, and court documents. Using clips from films of the period, as well as footage of testimony from the hearings, a complete sensory environment is created

Photo: Courtesy of Glenn Castellano, The New York Historical

When the show opened in April, the president and CEO of The New York Historical, Dr. Louise Mirrer, said, “Our aim with Blacklisted is to prompt visitors to think deeply about democracy and their role in it. The exhibition tackles fundamental issues like freedom of speech, religion, and association, inviting reflection on how our past informs today’s cultural and political climate.”

The narrative begins with a black screen carrying the words, “The Blacklist 1947.

It describes how, “In 1946, Conservatives took control of the House and Senate.” Aided by “vocal anti-Communists,” they pressured the executives of the movie studios to root out any in the industry suspected of having present or previous ties to Communist ideology.

Guiding the viewer, the accompanying text for the items on display underscores that America has previously been tainted by illiberalism, prejudice, and movements driven by anxiety and apprehension. It gives the dates of the Blacklist as 1945-1960 and ascribes its rise to the post-World War II reaction to the spread of “global Communism during the Cold War. (1947-1991)” More specifically, it references the apprehension stoked around the “power and influence of the Soviet Union.”

At stake were First Amendment rights, which fell by the wayside when “political and corporate interests superseded civil liberties,” driven by a specific vision of national security. As a result, people lost their jobs. Others, afraid of the same fate, either remained on the sidelines or succumbed to coercion to save themselves.

There is plenty of backstory. When the Espionage Act of 1917 was enacted, its goal was to disallow “false statements” that could hamper the war effort. Soon, the Act became an instrument of censorship, with foreign-language newspapers as prime targets. The Sedition Act of 1918 criminalized speech or printed matter that qualified the American government with commentary characterized as “contempt, scorn, or disrepute.”

The efforts to muzzle speech and dissension intensified in 1919 and 1920, after a steel strike, when Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer spearheaded federal raids on organizations, resulting in the arrest of thousands. During this period, Emma Goldman was deported, the labor movement lost traction, and J. Edgar Hoover got his start as a rookie agent overseeing the raids.

A copy of the New York Tribune from January 1920, overlaid with white lettering on a red background, shows the context of “The First Red Scare” with headlines screaming, “3,000 Arrested in Nation-Wide Round-up of Reds.”

Examined is the impact of the Great Depression, detailing the economic landscape of the 1930s and 1940s, which prompted many to search for alternative solutions. The Communist Party USA (CPUSA) was an interracial organization that actively sought equality for Black Americans. Jewish Americans were also heavily involved (almost fifty percent of membership) due to their political beliefs and concern about rising worldwide fascism and Nazism.

Before America entered World War II, several films addressed the crisis in Europe. “Confessions of a Nazi Spy” (1939) and Charlie Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator” stand out as examples. However, Congressional representatives who did not want to see America get involved in the fight called out specific films as being enmeshed with “a Jewish plot to push the country into war.” Pearl Harbor temporarily changed the equation as Roosevelt enlisted Hollywood to create content and storylines supporting the war effort.

A “Guide to Blacklist Terms” frequently used during the era is outlined. Fellow Traveler and Red-baiting are included, along with descriptions of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), and the New Deal.

And then it’s time for Senator Joseph McCarthy.

The name of the Republican from Wisconsin has become synonymous with the era, with McCarthyism as a descriptor of discrediting a person based on their political beliefs. Although he wasn’t part of the Hollywood Blacklist hearings, McCarthy’s allegation of having a list of Communists in the State Department and the Military kept him in the spotlight from 1954 through 1957, when the Senate censured him.

When HUAC subpoenaed forty-five individuals in the Hollywood sphere, from actors to screenwriters and executives, the composition of the Committee was predominantly Republicans and Southern Democrats, who vehemently opposed the tenets of Roosevelt’s New Deal. Witnesses were categorized as “friendly” or “unfriendly.” Those considered friendly benefitted from Congressional immunity. The infamous question, “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” was posed to the latter. There were also inquiries about their memberships in “professional guilds.” The one director and nine screenwriters who refused to answer those two questions were charged with contempt of Congress. They became known as The Hollywood Ten

L to R: Samuel Ornitz, Ring Lardner Jr., Albert Maltz, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Herbert Bieberman, Edward Dmytryk), 1950

Courtesy of Photofest

Ronald Reagan gets his own section of information. At the time, he was serving as the president of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG). He didn’t publicly endorse the Blacklist. However, he confidentially gave over fifty names to the FBI of those he believed had ties to some iteration of Communism.

HUAC disproportionately targeted Jewish Americans during the Red Scare. If a witness was considered unfriendly, they were rarely allowed to deliver a statement. Yet writer and Hollywood Ten member, Samuel Ornitz, was able to submit, “I wish to address this Committee as a Jew, because one of its leading members is the outstanding antisemite in the Congress…I refer to John. E. Rankin.” The Congressman was also known for his virulent racism and was called a “white supremacist.”

The Civil Rights Congress (1946), which worked to secure justice for Black Americans, especially in the South, published a pamphlet calling out HUAC. In response to their efforts, the HUAC labeled them as subversive. The group dissolved a decade later.

In November of 1947, in response to the HUAC hearings, Hollywood studio heads met in Manhattan at the famed Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, which became known as the Waldorf Conference. On November 25, they released a statement affirming their commitment not to hire anyone with any connection, past or present, to the Communist Party.

At that time, they also announced the dismissal of the Hollywood Ten. Finances and profits were the top factors. Louis B. Mayer, head of MGM, verbalized that the “first job must be to protect the industry and draw the greatest number of people into theaters.”

The exhibit makes a point to acknowledge the short-lived pushback from top film stars who formed The Committee for the First Amendment. In a statement calling out the “moral wrongs” of the hearings, the group included well-known names. Many would end up blacklisted. Others would publicly recant their original views. A page from the March 1948 issue of “Photoplay” features a photograph of Humphrey Bogart with the title, “I’m no Communist.”

Photo: Courtesy of Glenn Castellano, The New York Historical

In 1950, the Hollywood Ten, convicted of being in contempt of Congress for refusing to answer questions posed by HUAC, received jail sentences of up to one year in federal prison. They sought to overturn the decisions, but a federal court upheld the sentences, ruling that the First Amendment did not apply to their case. After the Supreme Court lost two of its most progressive members to unanticipated deaths, the new Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

And so, the years of shattered careers, uprooted lives, and fractured families commenced.

Writers were able to use what were termed “fronts,” submitting their work under the name of other authors who had no accusations against them. However, actors and directors didn’t have that option. Many moved to another country, while others began new livelihoods such as teaching. Many ended up aiding HUAC when they believed they had no other options. A noteworthy anecdote references the actor Robert Vaughn, who chose to attend graduate school, where he made HUAC the theme of his dissertation.

Americans associated with the Communist Party had to “forfeit” their passports. Those who had escaped to other nations were forced to relinquish their passports to the American Embassy in the country where they were living. It wasn’t until 1958 that the Supreme Court restored passport rights.

The exhibit highlights individual stories of those who were adversely affected, those whose lives ended due to health issues related to stress, and those who took their own lives. A panel entitled

“Premature Death” featured a list of individuals, including Philip Loeb, who committed suicide. A photograph of Loeb describes his contributions to the fields of acting and labor. He was a cast member of the well-received television show “The Goldbergs” and a leader in the Actors’ Equity Association. His name was familiar to me because my mother had studied with him at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts.

Actor John Garfield, the child of Russian Jewish immigrants, had been active in anti-fascist and anti-Nazi movements. His wife had been a party member, but he had never been a Communist. Blacklisted in 1951, he died of a fatal heart attack at 39 years old.

The composition of the HUAC committee members, which was rife with racists, antisemites, and opponents of the New Deal, created an incendiary environment. According to the exhibit’s accompanying material, numerous HUAC committee members viewed their mission as shepherding a return to the social order of entrenched hierarchies that Roosevelt and World War II had dislodged. Klu Klux Klan defenders amplified a white supremacist agenda and went after Black actors with a vengeance. Paul Robeson was a top target, as he was outspoken about his beliefs as a Communist.

Also examined and motivating the HUAC inquisitors were the matters of “gender and sexuality.” Within a framework that feels all too familiar, they designated heterosexuality, patriarchy, and the framework of the nuclear family as the norm. The concept of gender equity was seen as the outgrowth of Communist beliefs.

The “Lavender Scare” was part of the effort to root out the “enemies within.” The 1953 Executive Order 10450, signed by President Eisenhower, ousted gay and lesbian employees from federal jobs. It existed in tandem with the second Red Scare. The story of choreographer and dancer Jerome Robbins, whose parents were Polish Jewish immigrants, is recounted. A previous member of the Communist Party, Robbins gave names to HUAC in an effort to protect his privacy and advance his career in film.

In the early 1940s, the FBI had already begun looking at movies through a specific lens to determine whether any Communist subtext or “messaging” was apparent. Information on several classic films is offered. For each, there is a synopsis, awards, Blacklist connections (Communists appear in red), with an FBI analytical overview. An example of the depth of insight is encapsulated in the single-sentence appraisal of the 1946 Frank Capra classic, “It’s a Wonderful Life.” The assessment stated: “This picture represented a rather obvious attempt to discredit bankers.”

Some of the actors driven out of the film and television industries found a modicum of relief in the New York theater. In 1951, the Actors’ Equity Association voted for a resolution condemning the Blacklist. In 1953, Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” won the Tony for Best Play of the year. It was widely recognized as an unequivocal indictment of HUAC.

The exhibition posits that the Blacklist “does not have a clear end.” During the 1960s, many screenwriters and actors delivered important creative output after their banishment. In the 1980s, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) began the task of “restoring credits” to those Blacklisted writers whose names had not appeared on their work. By 2000, the correct credit lines had been reinstated on 95 percent of films through new prints and home video.

In 1960, Dalton Trumbo received recognition for his movies “Spartacus” and “Exodus,” which opened the door. His script for “Roman Holiday,” which won an Oscar for best story in 1953, had been given to Ian McLellan Hunter, a front. His wife accepted a posthumous award for this accomplishment in 1993.

In Watkins v. United States, a 1954 case in which HUAC subpoenaed John T. Watkins, an activist with the United Auto Workers (UAW), he said he refused to “ answer certain questions that I believe are outside the proper scope of your committee’s activities.” After being convicted of contempt, he appealed to the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Earl Warren pronounced, “Who can define the meaning of ‘un-American’?” It had taken the Supreme Court of the United States eight years to roll back the powers it had bestowed on HUAC.

In addition to being a thorough presentation that delves into a previous period of ignominy in American history, the parallels to today’s America are frightening.

Yes. It can happen here, and in a more nefarious way than in the 1950s, because of technology.

The questions of moral choices, speaking out against government injustice and malfeasance, and First Amendment freedoms are on the table.

The museum produced a “Family Guide,” with a paragraph that asked an important question for people of all ages:

“Political blacklists are a way of taking away people’s voices. If you are not allowed to participate or speak, no one can hear your ideas. You might lose friends, jobs, and your home. As you go through this exhibition, think about who is being allowed to speak and who is being silenced.”

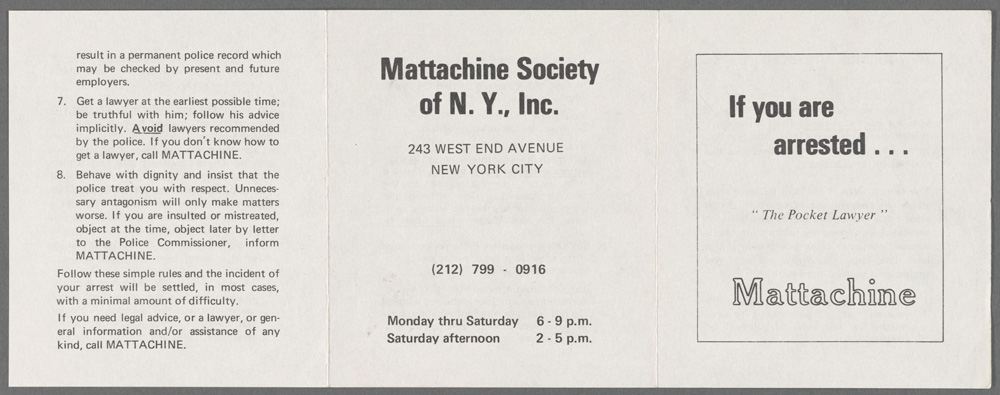

Mattachine Society of New York “If You Are Arrested…”, New York, NY, 1960 Courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections

Founded in New York in 1955, Mattachine Society was one of the earliest gay rights organizations and part of the homophile movement. While protecting the privacy of its members, Mattachine provided resources to LGBTQ+ New Yorkers navigating discrimination, harassment, and the risk of arrest during the Lavender Scare.