A Conversation with Amaranth Ehrenhalt

In what was previously a school building on 108th Street in East Harlem, I entered into the universe of artist Amaranth Ehrenhalt. I first saw her work in an exhibition at the Anita Shapolsky Gallery in New York. She is currently included in the gallery’s group show, “Abstract Approaches,” running through March 28.

Having briefly met Ehrenhalt, I became intrigued by the statuesque, older artist who had a backstory that included art world history in both the United States and Europe. I was inspired by her steadfast commitment to her art, and curious as to why she was—for the most part—under-the-radar. Here was a female artist, almost 90 years old, who was still producing.

I had to know more.

When Ehrenhalt opened the door to her apartment, I walked into a foyer that had boxes, flat files, and stacked paintings on either side. Deeper into her space was a passageway to the area that she had designated as her studio. A folding rack, filled to capacity, held prints and works on paper. Canvases were hanging on the walls and there was a painting on plywood in progress. African masks and Berber pottery from North Africa, collected on her travels, co-existed with ceramic bowls and plates made by Ehrenhalt in Paris. Examples of her virtuosity were displayed via her sculptures, mosaics, tapestries, and prints. It was as if an artist in a frenzy had touched every surface with their talent. “Yes,” Ehrenhalt informed me, the pillows on the sofa were her design as well. She was wearing a long colorful scarf, one of her textile projects.

The kitchen blended into the work area. A dining tabletop was composed of her ceramic tiles. Framed prints were in a narrow hall. Articles and images pulled out of the New York Times were tacked up for reference. Ehrenhalt explained the layout of her duplex—which is totally geared to her practice. She said, “It’s the first thing I look at when I get up in the morning, and the last thing I see before I go to bed.”

Ehrenhalt exudes an aura of vitality; one would be hard pressed to guess her age. She is tall (“I was 6’ when I was 14 years old.”), with large, strong hands. Listening to a series of narratives, in response to my questions, it’s easy to imagine the vibrancy of her 20-something self. One of those stories was featured in the September 2012 issue of Vogue, where Ehrenhalt wrote of her days in Paris and friendship with sculptor Alberto Giacometti.

Beginning at the age of four, Ehrenhalt had a strong desire to paint. She grew up in Philadelphia, in modest circumstances. Her parents were first-generation American Jews, with old-school ways. Ehrenhalt clearly remembers, “Art was all that I ever wanted to do.” For a girl born in 1928, it wasn’t going to be smooth sailing. However, she did get an early start. A public school teacher told the principal that Ehrenhalt needed to be placed in the “creatively gifted” Saturday morning program at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Rather than leave the museum premises when her class was over, and unbeknownst to her parents, Ehrenhalt wandered around the galleries looking at everything from El Greco to Cezanne. She envisioned a future for herself making great works of art.

On a full tuition scholarship at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Ehrenhalt took classes in perspective, anatomy, still life, portraits, and the science of materials. One afternoon per week she attended an art history class at the Barnes Foundation, taught by Violette de Mazia. Ehrenhalt said, “It was an incredible grounding.” She added, “I came to know Violette and Dr. Barnes quite well.”

Determined that she would travel to Paris, Ehrenhalt worked and saved money throughout her teens. It was to be the next step after she graduated. Ehrenhalt sought support for her plans from her father—knowing that if he didn’t offer his blessings, she was going anyway. He didn’t approve, and Ehrenhalt was on the boat to France. She built camaraderie with the other students en route to exploring life and education abroad.

Settling in at the American building at the Cité Universitaire, Ehrenhalt met two American girls who invited her to hitchhike to North Africa with them. Rides were picked up with truckers from Les Halles market, headed to the south of France. After reaching Casablanca, Ehrenhalt journeyed on to Marrakesh. As if reliving the sights and sounds Ehrenhalt said, “Everything you see, you take in like a sponge. And I always had a sketchbook with me.”

It was at this time, at a youth hostel, that Ehrenhalt encountered another young artist—Friedensreich Hundertwasser (then known as Friedrich Stowasser). A black and white photograph of the two of them from this period sits on Ehrenhalt’s table, framed in silver and draped with beaded necklaces. Ehrenhalt related how the two of them crossed North Africa together, on the way to Sicily. She was the subject of three of his portraits.

Their parting came as a result of Hundertwasser’s return to Vienna, due to family concerns. Ehrenhalt continued on to Rome. When I asked her about her decision to continue solo—thereby ending an important relationship—she replied, “My first true love is, has, and always will be art.”

In Rome, needing money, Ehrenhalt secured a job teaching English. Continuing to paint, she sold works sporadically. Ehrenhalt developed relationships with other artists, including Alberto Burri. When his American dealer, Martha Jackson, came to Rome to make arrangements for his upcoming exhibit, Ehrenhalt served as his translator.

When Ehrenhalt returned to America, she moved to Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. The apartment she shared with three girls was so small that they had to keep their clothes under the beds. She eventually found a larger place, and began doing her artwork there. She spent evenings at the Cedar Tavern, where she met Franz Kline, Al Held, and Ronald Bladen. The evening before she left for a short excursion to Paris, Willem de Kooning told her, “As soon as you get back, call me. We’ll have dinner.”

It didn’t happen. The trip stretched out—indefinitely. She met the man who would become her husband, also an American artist. They each painted, showing their work in their home salon-style, and living off the sales. As Ehrenhalt describes it, circumstances didn’t sound easy. After two children and fifteen years of a difficult marriage, she got divorced. However, she made a point of sharing, “I couldn’t imagine my life without having children.”

Despite the hardships, life in Paris had plenty to offer. Ehrenhalt became part of a circle of expatriate Americans that included Shirley Jaffe, Sam Francis, and Joan Mitchell. It was during this period that she changed her first name from Roslyn to Amaranth. “I love words,” she remarked. “That’s why all my works are titled.”

Perhaps the most critical connection Ehrenhalt made while in Paris was with Sonia Delauney. Impressed by her abilities, Delauney became a patron. She told Ehrenhalt, “You’re a very talented artist. I’d like to see more of your work.” Realizing that Ehrenhalt was struggling, Delauney arranged for her to buy paints on her account. Ehrenhalt shared an anecdote about Delauney sending over Christmas dinner, art books, and presents for her son and daughter. Ehrenhalt met Alix de Rothschild, who purchased one of her pieces. The day the Baroness made a studio visit to Ehrenhalt’s flat, it was extremely cold. The following day, de Rothschild sent a heater to the family.

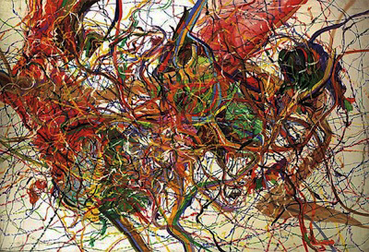

Ehrenhalt became well-integrated into the European art scene, with a core of collectors, numerous exhibitions, and frequent reviews. As early as 1962, poet and critic John Ashbery singled out her painting, Jump In and Move Around, in his review of the “New Forces” exhibition at the American Center. He wrote in the International Herald Tribune, “A key figure among these 31 artists from 14 different countries might be the American Ehrenhalt.” Discussing the canvas he stated, “It is both an excellent example of New York School abstraction (lush colors, fluent brushwork, bustling composition) and an attempt at a new possibly eerie form of figuration. The large flat areas juxtaposed with smaller, detailed ones seem always on the point of resolving themselves into a landscape or a portrait.” Ehrenhalt pointedly emphasized, “There’s no first name used, so you don’t know what gender I am.”

Jump In and Move Around, 196I

Jump In and Move Around, 196I

Oil on Canvas

59” x 77”

Ehrenhalt went on to specify the list of collections she was part of in France, including the Bibliothèque nationale de Paris. “Being in America—it’s so big. She said, “If you’re an artist in a small country, you get much more support.”

Returning to the United States in 2008, in order to be close to extended family, was a definitive transition. Ehrenhalt had a rude awakening regarding the art scene. There was palpable frustration evident as she lamented the lack of opportunities for an artist still producing prolifically at a later career point. “My newest work doesn’t have enough exposure,” she stated with exasperation.

I asked Ehrenhalt how many pieces she estimated she had in her studio. “I have a mattress on top of flat files! I have thousands of pieces of work,” she exclaimed.

Ehrenhalt was one of fifty-eight artists in the book American Abstract And Figurative Expressionism: Style Is Timely Art is Timeless (2009), along with Mark Rothko, Lee Krasner, and both Elaine and Willem de Kooning. Her painting, Umatilla, is scheduled to be included in an exhibit at the Denver Art Museum in 2016.

Umatilla, 1959

Umatilla, 1959

Oil on Canvas

59” x 87”

Being frank about the art world, Ehrenhalt reflected on the past and the present. “It’s hard to survive. In my generation, women had to either be financially independent or have connections with a top male artist.” Commenting on the gallery system, she said, “A gallery can make or break an artist. They can take a young artist and put them on the map.” Of much of the work that she sees these days she admits, “It doesn’t touch me in a deep way.”

In 2006, Ehrenhalt was part of a show at the Sidney Mishkin Gallery, entitled Encore: Five Abstract Expressionists. The subtitle was, “Less Well-Known Figures Emerge, Extending the Canon.” Her paintings have been acquired by American collections including Philip Morris, Downey Museum of Art, and the Hirshhorn Museum. One of her catalogues featured a quote from Joseph Hirshhorn stating, “What makes an artist important is the fact that she develops her own language, which is what Amaranth is doing.”

Number 9 in the Series of 8, 1973

Number 9 in the Series of 8, 1973

Watercolor and Gouache on Arches paper

30” x 22”

Collection: Hirshhorn Museum

Showing me images of a series of oil on canvas paintings called Poggibonsi I—V, Ehrenhalt said, ”The more you see my work, the more you love it, the more you can’t live without it! I had a collector who bought one work from this group, and then he came back to purchase another and another—until he owned all five.”

Poggibonsi I, 1999

Poggibonsi I, 1999

Oil on Canvas

77” x 51”

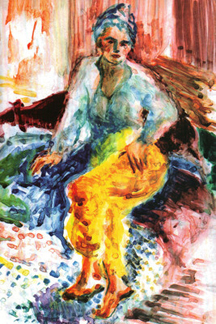

As early as My Mother, there are precursors to what will become Ehrenhalt’s vocabulary for handling paint. Her use of shorthand—through pattern—to designate areas of the bed and floor, suggest the approach she will employ later on to evoke space and depth.

My Mother, 1946

My Mother, 1946

Watercolor on Paper

15” x 11”

Six years after Jump in and Move Around, Ehrenhalt explored a different direction in Wend. Using a grid format over a mixed palette background, she introduces a third motif—that of a sinuous snake-like form. Her gradations of color reference the school of Orphism. Enclosed in the tail end is a photograph of the artist.

Wend, 1967

Wend, 1967

Oil on Canvas

64” x 51”

In Snow Today, geometric and organic shapes share the paper surface with an energy of movement that refuses to be contained. As in future work, Ehrenhalt combines tightly manipulated forms with broad areas of wash.

Snow Today, 1974

Snow Today, 1974

Watercolor and Gouache on Arches paper

22” x 30”

A year later, Ehrenhalt transformed her imagery into a large-scale tapestry. In discussing the woven pieces, Ehrenhalt made clear that she was hands-on in the process, making decisions about all aspects of the project.

Euphrasia, 1975

Euphrasia, 1975

Tapestry

102” x 75”

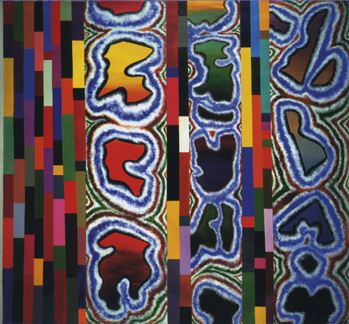

Constantly experimenting, Ehrenhalt takes previously established stylistic elements, and does a modern day “mash-up” of seemingly unrelated components. In the 1980s, she worked in acrylic, combining opaque areas of color bands with free flowing amoebic forms.

Alembert, 1987

Alembert, 1987

Acrylic on Canvas

79” x 85”

Ehrenhalt returned to using oil paint by 1991, engaging active stroke marks alongside scumbled patches. Throughout her oeuvre, color is primary. Tonalities are vibrant and intense. Each hue is consciously placed, creating a tense interaction within the visual field. During the same time period, responding to her paintings with works on paper, Ehrenhalt used line drawing and crayon-colored areas to explore another iteration of her large-scale work.

Susquehanna, 1991

Susquehanna, 1991

Oil on Canvas

46” x 36”

In the late 90s, Ehrenhalt took on the challenge of doing individual works that could be configured in more than one way. She coined the term of “Double Look” to describe the possibility of viewing a diptych in two different configurations, using the process of inversion.

Zalmon (Dyptych: Two Views), 1997

Zalmon (Dyptych: Two Views), 1997

Oil on Canvas

77” x 60”

Ehrenhalt showed no signs of slowing down in the new century. If anything, she expanded her repertoire to include the new medium of monotype.

Greg C, 2007

Greg C, 2007

Monotype

20” x 28”

Having previously worked in etching and woodcut, I asked Ehrenhalt, questions about her techniques. “I just experimented,” she replied. “The first print I did was a woodblock. I used a spoon on the back of the paper!”

Querceta,1991

Querceta,1991

Etching

33.50” x 24.50”

Moving into three-dimensionality, Ehrenhalt combined her painting imagery on wood with the structure of marble. In a moveable, pivoting sculpture, Ehrenhalt both challenges and enables the viewer to observe her creation in several ways.

Black Bear Square, 2005

Black Bear Square, 2005

Marble and Painted Wood

20” x 20” x 4”

During seven decades of exploring her artistic voice, Ehrenhalt has achieved innumerable permutations of visual expression. She told me with pride that her public art project in Bagneux, France, was so beloved by the local residents that it had never been marred by graffiti.

Douze Sourires, 1990-1991

Douze Sourires, 1990-1991

Mural at Bagneux

Glazed Ceramic Tiles

481′

Recognition as an artist is a combination of talent and luck. Sometimes it’s about being in the right place at the right time. As I spoke with Ehrenhalt about her career trajectory, she said definitively, “I feel certain, and there has never been any doubt in my mind, that my paintings could stand up next to the best of either generation of the Abstract Expressionists—male or female.”

Regardless of what the curators and “decision-makers” of today’s art scene are looking for, Ehrenhalt is not waiting for anyone’s validation. “I know what I want to do,” she said resolutely, “and I’m my own best critic.”

Before I departed, Ehrenhalt reflected, “When I paint, nothing else exists. It’s just so intense.” She added, somewhat dryly, “When I stop painting, I’ll already be dead.”

Hopefully, there will be an opportunity for her to show the full range and depth of her works in a retrospective in the near future.

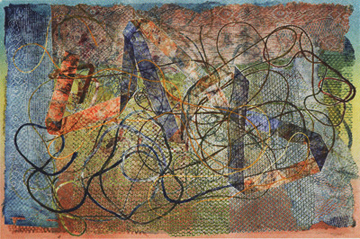

Cascara 2, 2004

Cascara 2, 2004

Gouache on Arches paper

30” x 22”

Photos: Courtesy of Amaranth Ehrenhalt

This article is from the series “Evolution of an Artist”