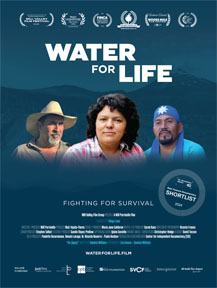

“Water for Life” – Fighting for Land Rights in Latin America

At a time when Americans face each new day with trepidation as the country’s laws and freedoms come under attack, the documentary “Water for Life” stands as an example of how values can triumph. The road isn’t easy, and there are setbacks along the way, but that’s part of the journey.

Director Will Parrinello, who has made Indigenous rights and the environment key subjects in his thirty-five-year career, delivers a film (available to stream on PBS) demonstrating the conflict between power, money, and influence against an ethos that considers people over profits and respect for the earth over exploitative usage. Three individual narratives of Latin American defenders of the environment share the common bond of respect for the spirituality of nature, and what it gives back to those who understand the connection between all living things.

What will people who follow this path do to protect the sanctity of their land and its resources?

Alberto Curamil is the Chief of the Mapuche people, who comprise 84 percent of the Indigenous population in Chile. His great-grandfather fought to keep white men from crossing the Malleco River when the Spanish first invaded the territory. The Mapuche have been on the land for thousands of years.

When referencing his ancestors’ past and how their land was stolen, Curamil said, “Now it’s the corporations.” The target is water resources, specifically the Cautín River, which Curamil calls “the lifeblood of our territory. It contains a spiritual force.”

It’s all about building hydroelectric projects, thousands of them. The effort began in 2010 with construction slated for the “heart of ancestral lands.”

Máximo Pacheco, the former Chilean energy minister, believed that resources were “abundant” and could facilitate renewable energy. Manuela Royo, Curamil’s lawyer, clarified the problem. “Several hydroelectric projects were approved without any consideration of them being in Indigenous territory.” The constitution of Chile does not include a recognition of “the existence of Indigenous People.”

The (UN) ILO Convention 169 outlines that in advance of any action taking place on Indigenous land, the people “must be consulted.” As Parrinello clarified when we spoke, “ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples’ rights was developed in collaboration with the United Nations, paving the way for the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). The ILO and UN work together to protect and promote the rights of Indigenous and Tribal peoples, with Convention 169 providing a legally binding framework. The United Nations plays an important role in supporting 169’s implementation while promoting broader awareness of Indigenous rights. However, UNDRIP is a declaration, while Convention 169 is a binding international treaty for those countries that signed it.”

The government of Chile released a report qualifying the area as being without Indigenous people. Journalist Ana Rodriguez is on hand to challenge that determination. Drawing such a conclusion would require extensive fieldwork, costing significant money and time. That in itself would serve as an impediment to moving forward with extraction.

In 1973, Augusto Pinochet took power in an American-supported military coup, ousting the democratically elected President, Salvador Allende. Pinochet’s seventeen-year dictatorship escalated problems for the Mapuche. The government privatized the country’s natural resources, gave land to the timber industry, and even traded water rights on stock exchanges.

A dilemma arises for the Mapuche as drought sets in, resulting in water shortages. If there is no “legal” right to the water that traverses their lands, usage can result in court cases claiming theft.

When Curamil goes to Santiago to speak about these concerns, he self-identifies not as an environmentalist but as a Mapuche Chief defending his land. Mauela Royo, Curamil’s lawyer, asserts that the government’s environmental report was deliberately falsified when they claimed that the project would have “no impact.”

In July 2014, Curamil and his legal team take on the Chilean government. It is about a larger cause than the concern of the water itself. It is an element of a larger confrontation, which is to reclaim ancestral territories.

Anger and frustration lead to acts of violence. Timber trucks are set on fire, along with other incidents of sabotage against the forestry companies. Like any other movement, the anti-mining ranks aren’t monolithic. In response to accusations of terrorism, Curamil responds, “Our life is at stake.” His wife delineates, “Neither jail nor death can stop the struggle.”

Two years after starting the legal case, Curamil has his day in Chile’s Supreme Court (2016). They hand down a 4-to-1 decision in favor of Curamil. The Doña Alicia hydroelectric project is canceled, as are all other plans for the Cautín River. The success is overshadowed as the powers that be see Curamil as a threat to future potential proposals. Curamil is ensnared by trumped-up charges of robbery in 2018, along with two other men. Despite no evidence, he is sent to jail. His young daughter, Belen Curamil, steps up to take his place while he serves eighteen months—waiting for his case to be heard. In 2019, a court of appeals in Temuco acquitted him of all charges. It’s clear that his activism was on trial—and that his time spent incarcerated was as a political prisoner.

* * * *

In El Salvador, Francisco Pineda, a subsistence farmer, is embroiled in a fight to protect the land he loves from a company that will stop at nothing to achieve its goals: The Pacific Rim Mining Corporation.

They touted themselves as a “socially and environmentally responsible company” (as noted on their signage for their $1.6 million El Dorado mining undertaking). The mayor of San Isidro, José Bautista, tried to assuage fears, insisting that the company wasn’t coming into the community to exploit them. He pointed to the school classrooms and hospital improvements the company had undertaken.

The film shows Thomas C. Shrake, President and CEO of Pacific Rim Mining, testifying about the El Dorado project, claiming that the mine was designed to maximize environmental concerns. He stated, “The ways we protect the water are numerous.” He also states that Pacific Rim employees are told to use “Gandhi as a behavior model.”

(Note: The Canadian-Australian company OceanaGold acquired Pacific Rim Mining in 2013. They sold El Dorado in 2019.)

Water availability is a significant problem in El Salvador, especially as 90 percent of surface water is contaminated. The local residents had major concerns when a river dried up in 2004. They followed the river to its source and found that Pacific Rim had installed pumps extracting water in such high volumes that Pineda explained that in one hour, they had pumped out the same amount that an “average family” would use in three decades.

Gold mining uses extensive amounts of water while releasing lead and arsenic, both heavy metals. The information that two tons of cyanide per day are used in the mining process is paired with images of children in the river and women washing clothes. DuPont cans of cyanide are on the scene as viewers learn that the amount equal to a grain of rice is deadly to humans.

Pineda evangelizes about the hazards to the local population. He organizes twenty-six groups while initiating the Cabañas Environment Committee. After Mayor Bautista declines to get involved, a race for a new mayor is underway.

It’s impossible to look at the political dynamics without considering the impacts of El Salvador’s brutal civil war (1972-1992). A continued fear of confronting the powers in charge remains. During the struggle, over 70,000 civilians were killed by the military and death squads. The FMLN left-wing rebels promised equality and social justice. The Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) is anti-Communist and promoted private land ownership over land rights.

Pineda defined his campaign as an authentic quality of life concern against financial profits. He supported a law that “prohibits metallic mining in El Salvador.” He spearheaded marches accompanied by Catholic clergy, whose backing gave gravitas and momentum to the anti-mining cause. Possibly due to national polling findings in 2009 taken prior to the election, President Mauricio Funes banned all mining, officially ending mining in El Salvador.

With this door closed, Pacific Rim strikes back by taking a legal route. They sue El Salvador for $300 million on the premise of a violation of the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA). It is a move, that if successful, would irrevocably impact the country’s economy.

In the summer of 2009, Pineda began to receive death threats. A colleague is slain and dumped in an abandoned well. Pineda hires bodyguards. By December, there is another activist killing and people are disappearing. The re-elected mayor suggests that the anti-mining groups were the culprits, creating a “martyr for the cause.” Also offered as a deflection is the excuse of “gang activity.”

It takes ten years, but El Salvador wins its case against Pacific Rim. The company must reimburse the country $8 million in legal expenditures. The Attorney General of El Salvador gave specific credit to the people of San Isidro. In 2017, the Congress of El Salvador became the first country to “ban the mining of gold and all other metals.” (Note: In December 2024, under President Nayib Bukele of Oval Office fame, the ban was overturned. The only opposition came from environmental advocates and the Catholic Church.

* * * *

Berta Cáceres stands as an example of courage and leadership to women, Indigenous rights advocates, and environmentalists worldwide. A defender of the Lenca people and the “sanctity of nature,” Cáceres fought to guard the Gualcarque River in Honduras. She elucidated, “It signifies life.” With its sustenance of medicinal plants and its necessity for growing food, Cáceres saw her fight to preserve the river as an “honor.”

National politics again is a backdrop. In June 2009, a constitutional crisis precipitated the removal of President Manuel Zelaya by the army (He was exiled to Costa Rica), despite the United Nations calling for his reinstatement. When interviewed, Zelaya asserted that the coup was in response to the “socio-economic policies that my government took to gain market freedom.” He suggested that his oil purchase from Hugo Chávez of Venezuela had antagonized European and American oil companies. During his time in office, he worked with Cáceres and recognized the claims of “ancestral land rights.”

The Lenca people, with a population of 450,000, are the largest Indigenous group in Honduras. Referencing the government allowing international businesses to come into Honduras, Cáceres informs, “We are experiencing one of the greatest handings over of sovereignty that we’ve seen in the past five hundred years.” She spoke of the takeover of river resources and the approval of over 1400 mining and hydroelectric concessions.

The Honduran company Desarrollos Energéticos SA (DESA) contracted with the state-owned Chinese company Sinohydro to build the Agua Zarca Dam on the Gualcarque River, a sacred site for the Lenca. Olivia Zúñiga Cáceres, the eldest daughter of Cáceres and Honduran ambassador to Cuba observed dryly, “After drug dealing, power generation is one of the top profit makers for the country.” Rampant corruption facilitates getting approvals for contracts and permits. The Honduran power structure is enmeshed with these dealings, from the government to the military. As ex-President Zelaya underscored, the country is run by elites with monopolies controlling everything.

Journalist Melissa Cardosa said, “The Honduran territory was practically handed over to transnational corporations and hydroelectric projects. They came with money, they came with a lot of prestige, and they came heavily armed.” The Honduran army evicted local farmers while DESA tractors ran over their planted crops. There was no compensation.

Into these conditions comes “crisis management” attorney Robert Amsterdam, retained by DESA. His website portrays him as a human rights advocate, but this assertion has been publicly challenged. On camera, he presents as condescending and disingenuous. One of his top quotes is, “Companies like DESA that go in and give them doctors and electrification and health care—if you’re a parent that’s what you want. These are people who don’t have the money to feed their children. Forget the environmental review—feed those children!”

Cáceres saw the circumstances quite differently. She said of DESA, “They came in like they owned everything.”

David Castillo is the representative running DESA and overseeing the Agua Zarca project. Aureliano Molina, an Indigenous rights defender, maintained that Castillo, always accompanied by armed police, was not forthright about his personal history. When his background was examined, they learned he was a West Point graduate with electrical and computer engineering expertise. His record also showed he had been an intelligence officer in the country’s armed forces. Those connections garnered him the ownership permits for the Agua Zarca hydroelectric development.

Cáceres organized town halls and over one hundred and fifty Indigenous assemblies and debates. She defined the reasoning behind the people’s rejection: “They didn’t want to damage or privatize their sacred river.”

Salvador Zuniga, former husband of Cáceres and an Indigenous activist, gives backstory on how the violence of the civil war in El Salvador pushed him and Cáceres to engage with “non-violent” strategies. Their goal was democratic self-governance while preserving and protecting communal lands. They co-founded the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH).

Construction that impacted the Gualcargue River began in May 2013. To prevent resistance, DESA used the military. In response, the Lenca community set up a roadblock with large boulders and tree stumps. They slept on-site, guarding it through inclement weather and harassment.

Two months in, a soldier randomly shoots into a group of protectors. He kills community leader Tomas Garcia and wounds his 17-year-old son. Soon after, Sinohydro terminated its contract with DESA and pulled out of Honduras. Farmers resumed their livelihoods; the military left. But the conflict wasn’t over. DESA’s new approach was to reestablish itself on the opposite side of the river—which is still Lenca territory. DESA created conflict and rivalry with the citizens of El Barrial, who supported the dam’s construction.

Threats against the physical safety of Cáceres began. Unmarked cars lurked near her house. Family and friends were anxious about her welfare. Cáceres acknowledged her fears but refused to be paralyzed by them. She knew they would come for her, and they did.

Cáceres was with Gustavo Castro, an environmental defender, when she was shot three times on March 2, 2016. In 2018, eight men were tried for her assassination. Unsurprisingly, the Honduran military and DESA were implicated. Seven of the eight accused were convicted, including DESA’s head of security. They received sentences of thirty to fifty years. Castillo, President of DESA, was found guilty of planning the attack. His term of imprisonment was 22 years and six months.

Cáceres children have picked up their mother’s struggle. They see her as “reborn” through the engagement of others. Indeed, her presence is everywhere: on walls, in street art, in the rivers, and at her gravesite, inscribed with the message: “Wake up humanity, there is no more time.”

When I spoke with Parrinello about his goal in bringing these accounts to the public, he told me:

“Now more than ever, we need stories of hope, showing how coordinated political action leads to positive change. Our film tells of community leaders from three separate Latin American countries who banded together with other like-minded people to make a difference. Grassroots action creates positive change in the world.

I hope that’s the greatest lesson of our film, particularly relevant to today’s political realities in the United States. Inspiring people to stand up, speak truth to power, and unite for the greater good.”

Image: Courtesy of Water for Life