A Conversation with Derrick Adams

In September, “Derrick Adams: Live and in Color,” opened at the Tilton Gallery in Manhattan. I sat down with Adams in Brooklyn, to talk about his work and career trajectory. We spoke at length, and went off on a few tangents—including the Koch Brothers, The Wiz, colonialism, and the leadership of Bayard Rustin.

At 44, Adams has plenty of exhibitions under his belt, both nationally and internationally. He received a Louis Comfort Tiffany Award, and has been in several shows at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Adams is included in Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art, which is currently at the Walker Art Center. He took part in Performa 05 and Performa 13. Currently a visiting artist at NYU, and a former member of the painting faculty at the Maryland Institute College of Art, Adams brings insights from his years at Pratt Institute, The Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and the Masters of Fine Art Program at Columbia University.

When I met Adams on the evening of his opening, he was dressed in pants and shoes that connected him to his collages. At our interview, only his camouflage printed socks spoke to his strong interest in color, patterns, and fabric.

Adams grew up in Baltimore, surrounded by a nurturing family that appreciated art. His hometown, known as “Monument City,” gave rise to his interaction with architecture as foundation, and led to his ongoing use of “bricks” as a motif. Adams’s upbringing among female relatives impacted his visual sensibility and frame of reference. He said, “When I think about flowers, I think about my aunt’s house—not Monet.” Being surrounded by a “collective consciousness of color and textiles,” whether it was his grandmother making “curtains and shelf-liners” or an aunt’s favorite scheme of mauve and grey hues, “set a tone.”

These concepts of a “formal response to how it is to decorate,” would translate into Adams’s room sculptures, which examine structure and the use of space in terms of self-reflection.

Modular Head Space (Sculpture with Details), 2014

Modular Head Space (Sculpture with Details), 2014

Collaboration with Industrial Designer Michael Chuapoco

52” x 48” x 36”

Photo: Courtesy of Derrick Adams

Adams spoke incisively about an integral part of his rearing—what he identified as the requisite need to acquire a “double consciousness.” He explained the lesson he absorbed as a young boy. It was the knowledge that “black folks had of themselves,” and the alternate view. That was, “The world looks at you as a monster—the other.” Adams gave the analogy of a young, black male child “skipping and then running,” only to have that simple activity construed as flight from an illusory crime. The need for an ongoing “dual identity,” as a means of survival for the adult black male, is a theme that repeatedly manifests itself in Adams’s work. Explored is a representation of an outer appearance in conflict with the truth of an inner psychology. Adams sees the majority of his work “residing in the idea of how outside influences impact the perception of self.”

Spending summers in New York City, with relatives, prepared Adams for his Pratt Institute experience. However, the educational structure yielded insights beyond studio art. Adams was the sole black student in his program. Speaking about the white students, Adams noted that they were not getting a “whole picture of the spectrum of cultural dynamics that include or don’t include.” Yet, Adams maintained that he “didn’t feel isolated.” He said, “I wanted certain key elements of intellectualism. I wanted to be challenged. I wanted to talk.” When I asked him if he felt compelled to push back on the lack of diversity he responded, “As an artist you just want to make art.” Adams connected to black artists through studio visits and other forms of interface.

The model of teaching that Adams encountered at Columbia motivated him to take a totally different approach in interactions with the students he would mentor. He is clear that it is “okay not to make what people understand.” Adams said, “I want to get my mind blown. Most professors want to be validated.” He added dryly, “Professors may look like you, but that doesn’t mean that they are supporting your point of view.”

While serving as curator for Rush Arts Gallery in Chelsea (1996-2009), Adams put the same philosophy into play, intentionally expanding his horizons to artists he didn’t already know about; broadening the curatorial mission from “emerging artists of color” to “underrepresented artists.”

Adams conversed about his process as an artist. He sees the act of creating as “visceral,” and the aftermath as a period of “academic analyzation.” Adams stated, “When you make a work, it shows people how you digest your ideas. Everything you’ve absorbed is realized in the work.”

Clearly, Adams relishes the act of art making—whether it is in the realm of performance, video, sculpture, or works on paper. He contemplated, “Being an artist doesn’t offer anything any more beyond peace of mind from doing the work. It’s therapeutic. For me, what I like about being an artist is [that] it comes from—and is separate—from you. It must be actual and out of your head.”

Adams is conscious of how his multifaceted artistic endeavors operate on the larger stage of the art world. Although Adams said he doesn’t see himself as a political artist, he did acknowledge, “Everything I make is a socially engaging work. I’m always questioning everything.” He emphasized, “I’m trying to pose questions for people to look at…by pulling back the curtain.” This gets back to Adams underlying premise—in art and in life: “Everything that we are is based on a specific construction.” Although Adams conveyed that he looks at art “as an intellectual journey,” he is equally concerned with how his art is presented, both in terms of the medium and the execution.

In his current show, Adams brings his exploration of race and “cultural context” to the table. Adams parsed his perspectives, in tandem with “the viewer bringing their stuff.” That can include the possibilities of the audience not understanding what they see, responding to what they perceive as a narrative, or having a strictly emotional experience. Adams described the latter as a “translatable feeling of, ‘I know that. I know what that’s about. I know how to use that information.’”

The exhibit is comprised of sixteen pieces. Six are mixed media sculptures. The remaining ten are mixed media collages on paper.

All are viewed through the framing device of a television set from the 1980s, models with faux wood paneling and large black knobs bisected by silver rectangular handles. The invitation had a reproduction of the test pattern developed by the Society for Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE). That layout forms the background and palette for the collages.

Adams’s appellation for his exhibition plays on the tagline that promoted TV shows evolving from their black and white status. Specifically, it is a reference to black entertainers entering the landscape of American broadcast television. Adams discussed the genesis of his imagery as having its origin in sitcoms, dramas, and newscasts featuring African-American characters—“morphed together, and communicating in a language that is “animated and larger than life.” Aware of the visual attraction of his vibrant tones, Adams said, “If I make artwork, you will be drawn to it.”

We returned to the themes of “content and context” as opposed to formalism; “surface” versus content; the use of “structural dynamics.” Yet at the core, stripping away the intellectualization, was a recognition of what Adams called the “formulaic image”—a representation of African-Americans based on a “turn-up the volume and exaggerated” portrayal. He terms it the “duplicitous presence.”

Talking about the influence of American black culture, Adams maintained, “It takes twenty-five to thirty years before it becomes diluted and filtered into the mainstream.” Adams underscored the “power of the media to represent.” The problem lies in the lack of veracity. Inevitably, that representation is stronger than an actual “engagement.”

Adams uses the metaphor of television as a “voyeuristic lens,” as well as a “portal.” In the Boxhead series, which Adams defined as “not gender specific,” he spoke about “attitudes and posturing, geometric forms,” and the use of “four perspectives in one object.” I related to the sculptures as female, reading them as a contemplation on black female identity, specifically focused on the hair as a reflection of self.

Boxhead Series (Left to Right) Boxhead #2, Boxhead #3, Boxhead #6, 2014

Boxhead Series (Left to Right) Boxhead #2, Boxhead #3, Boxhead #6, 2014

Mixed Media

23” x 28” x 19”

Photo: Courtesy of Tilton Gallery

The works are displayed on cardboard boxes. When I asked Adams about that choice, he defined it as an “anti-process action,” an alternative to the pristine pedestal traditionally used to “support art.” Adams considered it the “simplistic part of the piece,” and a nod to the concept of “things being unpacked and presented.”

The works are displayed on cardboard boxes. When I asked Adams about that choice, he defined it as an “anti-process action,” an alternative to the pristine pedestal traditionally used to “support art.” Adams considered it the “simplistic part of the piece,” and a nod to the concept of “things being unpacked and presented.”

The first collage we discussed was, I Come in Peace. A female black figure is portrayed in a crawling stance—or what could be construed as a sexual position. Wearing a leopard skin bikini, her hair is fashioned into a molded coiffure, reminiscent of a lion’s mane. Planes of colors divide the face, echoing the Boxheads. Solid bands of color from the television spectrum vocabulary are combined with snippets of the American flag (operating simultaneously as symbol and design), and camouflage material.

Adams sees the image as a “powerful” acknowledgment of the woman’s “self-expression.” She is conveying the concept, “Regardless of how you see me, I am offering myself as an idea.” For Adams, it boils down to the query, “How do you want to be known?” It’s Adams, putting it out there, challenging the spectator with the premise, “Is this a black woman in control of her options,” or an exploited performer buying into the “dynamics of a specific system of operation and financial gain?” Adams recognizes the ongoing debate (e.g., Beyoncé’s use of the backdrop, I Am a Feminist), as well as the inherent contradictions. I Come in Peace fulfills Adams’s goal of grabbing the viewer via an “emotional experience—the feeling of it.”

I Come In Peace, 2014

I Come In Peace, 2014

Mixed Media Collage on Paper and Mounted on Archival Museum Board

48” x 72”

Photo: Courtesy of Tilton Gallery

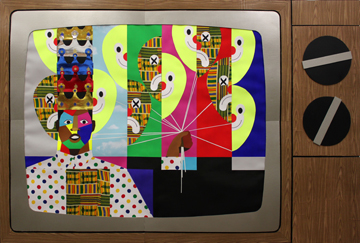

In King for a Day, Adams revisits the issue of African-American masculinity within American life. The figure is dressed in a white shirt with multicolored polka dots, incorporating a square overlay of kente cloth. A hand holds the string to twelve balloons. Seven are solid yellow, with smiles and rounded black eyes. Five are formed from the kente cloth, and have frowns and Xs for eyes. Adams describes it as his “riff on the idea of comedy and tragedy, outer appearances, and the duality of representation.”

King For A Day, 2014

King For A Day, 2014

Mixed Media Collage on Paper and Mounted on Archival Museum Board

48” x 72”

Photo: Courtesy of Tilton Gallery

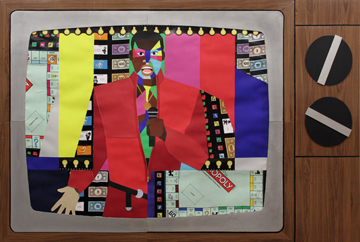

Fun and Games places the black male figure center stage, as game show host. He is surrounded by money, fragments of a Monopoly board, chance cards, and the possibility of landing in jail as part of life’s lottery. His demeanor presents a vigorous presence, but the subtext questions what Adams calls “strategies of success.” What does American life hold for the average black man? Does everyone really get an equal turn at the board, or are the dice loaded? The jail square brings to mind the stats that African-American men are imprisoned at much higher rates than their white male counterparts.

Fun and Games, 2014

Fun and Games, 2014

Mixed Media Collage on Paper and Mounted on Archival Museum Board

48” x 72”

Photo: Courtesy of Tilton Gallery

Commenting on the interweaving of entertainment and violence as an American preoccupation, Show Down examines beliefs and attitudes about guns. Adams pointed out, “People want to see those images on television, but not in real life.” The use of “bang flags” places the gun in the realm of a vaudeville gag, rather than as an instrument of lethal force. However, in reality, any connection of a black male with a firearm is interpreted as ominous, while a white man “bearing arms” is merely invoking his Second Amendment rights.

Show Down, 2014

Show Down, 2014

Mixed Media Collage on Paper and Mounted on Archival Museum Board

48” x 72”

Photo: Courtesy of Tilton Gallery

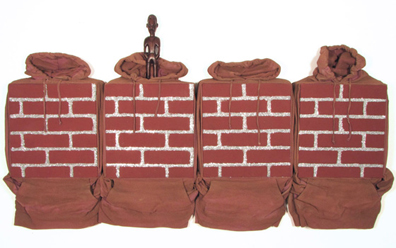

Underlying concerns parsed in “Live and in Color” can be seen in Adams’s previous works, both sculptural and two-dimensional. Dating back to 2008, Adams utilized the brick metaphor in combination with other objects to create statements. In Four in One (The Same League), several years before the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin, Adams incorporated the article of clothing that would become a flash point when a witness described Martin as, “A black male, wearing a dark colored hoodie.”

Four in One (The Same League), 2008

Four in One (The Same League), 2008

Painted Faux Brick Paneling, Hooded Sweatshirts, Glitter, Tempera,

Wood Sculpture

32” x 48” x 6”

Photo: Courtesy of Derrick Adams

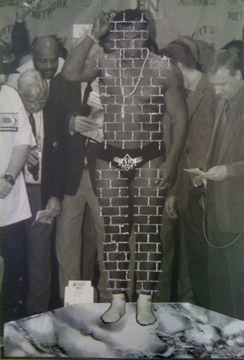

In The Statue, the bricks are overlaid on the persona of boxer Mike Tyson. Adams said he chose Tyson, “as Warhol used Monroe—for visual recognition.” Using the iconography of Tyson’s body like a “Michelangelo sculpture,” Adams scrutinizes how people were observing the young Tyson as “surface.” Altering specific elements of the traditional “weigh in,” the scale is transformed into a marble platform. Adams called it, “an allusion to the David.” Raising a number of questions Adams asked rhetorically, “Is it glory, sorrow, or objectification?” Hovering in the same the territory is the legacy of slavery—and the black male body in that narrative.

The Statue, 2009

The Statue, 2009

Digital Photograph and Metallic Silver Paint Overlay

27” x 17”

Photo: Courtesy of Derrick Adams

In his works on paper, Adams’s visual vocabulary consistently remains linked, even when using muted, neutral, and earth tones. In Black American Gothic two women are portrayed—one in a skirt, the other in pants. Both are wearing identically patterned shirts in different colors. Although they feel reminiscent of ancient Egyptian figure portraits, the torsos are rendered completely in side view. They each have an arm composed of a construction frame, carrying what could be construed as a purse, bearing the familiar brick pattern. A small African figure with a yellow hard hat stands on the uppermost grid line.

Black American Gothic, 2013

Black American Gothic, 2013

Mixed Media Collage on Paper

50” x 72”

Photo: Courtesy of Derrick Adams

Stepping Out incorporates sewing patterns, architecture, home design, and fragmented heads. This time, male and female figures are designated as the forms. Road signs, especially the traffic light, tie in with elements from Adams’s Video Interludes.

Stepping Out, 2014

Stepping Out, 2014

Mixed Media Collage on Paper

72” x 50”

Photo: Courtesy of Derrick Adams

Concerning his performance and video work, Adams referenced “learning how to think in a multi-dimensional way.” He embraces the premise of “embodiment through a complete practice—not just one source.” And if the results aren’t successful, that’s okay with Adams. He said, “You have to see it not work.”

In his videos, Adams frequently combines word usage, simplified language, and the format of educational television. He mentioned the influence of Jim Henson’s puppets, and how they were able to disseminate information that may otherwise not have been readily palatable. Adams stages a video segment titled, M is For… comparing well-known statements from Martin Luther King, Bob Marley, and Malcolm X, in a beginner’s format. It’s what he calls the “rearranging of familiar stuff.” His hope is that people will see those familiar things in a new way.

As our talk wound down, Adams reflected upon sharing his education through his art and deciphering it in a way that was understandable. He said, “We all have exposure to the same information. The difference is in how the artist presents it, and between what people are ready for versus what they need to know.”

As a young artist, Adams met Elizabeth Catlett. He asked her for advice. Her response was, “Make work.” Clearly, for Adams, there is satisfaction in working out his ideas through his art. He referred to that as, “the physical gratification of what existed in my mind.” He sees his oeuvre as a synthesis of what he took away from his academic experience, and objects from his background and personal history. He phrased it as, “My work is about y’all.”

Notwithstanding his success, Adams is clear about his objectives. He affirmed, “I don’t want to be a celebrity artist. I want to be known for my ideas.”

Shade, 2014

Shade, 2014

Digital C-Print

18” x 24”

Photo: Courtesy of Derrick Adams

This article is from the series “Evolution of an Artist”