“No Way But Forward: Life Stories of Three Families in the Gaza Strip”

For those who want to truly understand the challenges of daily life for Palestinians in Gaza, Brian K. Barber’s book, “No Way Forward: Life Stories of Three Families in the Gaza Strip,” offers a unique perspective by sharing the personal narratives of three men whose lives are traced from childhood to middle age. This in-depth approach provides unique insights. When the book came to my attention with words of praise from Anne-Marie Slaughter, Tareq Baconi, and Avi Shlaim, among others, I was primed for an experience that would deepen my knowledge about surviving on the ground for Palestinian individuals.

Barber’s writing style is entirely accessible, combining factual information with an engaging narrative that envelops readers in the intimate thoughts and emotions of the family, friends, and community of Barber’s subjects. It’s an essential read for those seeking a palpable look at the Palestinian challenges in Gaza.

A Professor Emeritus of Social Science at the University of Tennessee, Barber holds a PhD. He began work in Gaza in 1994, after an invitation from Brigham Young University to consult on the study of Palestinian families. Over the past thirty years, Barber has connected with more than 10,000 Palestinian households in Gaza, East Jerusalem, and the West Bank.

For people unfamiliar with the timeline of events in 1948, Barber delineates that when the “State of Israel was created,” approximately 700,000 to 750,000 Palestinians were either expelled or fled for safety. Four hundred villages were demolished. By the end of 1948, when a return to their former homes was not permitted by Israel, UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) was created. Tents eventually evolved into adobe structures, and then into cinder block.

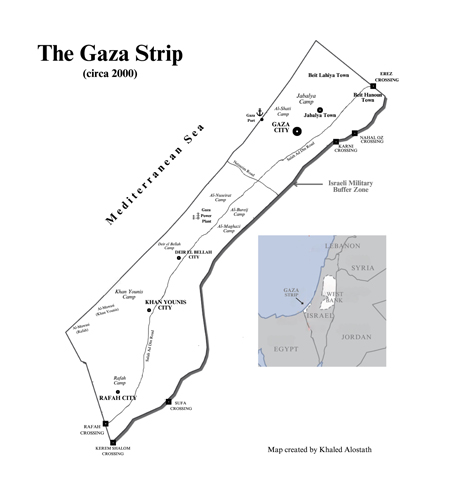

Camps familiar from the war, such as Khan Younis and Rafah, are described. There are eight camps in the Strip, housing over two-thirds of Gaza’s Palestinian refugees. Barber clarifies that this comprises the “original refugees” from 1948, plus “two generations of descendants.”

Barber traces developments in the Gaza Strip from the end of the 1948 war through the 1967 war and the seizure of Gaza. He notes that in 1971, “Israel began developing Jewish settlements in Gaza.”

To demonstrate how the lives of his subjects, Hammam, Khalil, and Hussam were shaped by the First Intifada (1987-1993), he gives a backstory on the regulations implemented over Palestinian life. This included Israeli control over the population, from the economy and culture to legal matters and land/water rights. Part of the approach included a psychological attrition—through censorship of media, changing the names of streets and towns from Arabic to Hebrew, the destruction of historical sites, and the repression of symbols of Palestinian identity.

Barber stated, “The Intifada was very important because that’s when the youth took to the streets in high numbers. To understand Palestinians, you must understand the Intifada. It was Palestinians asserting themselves. There was a lack of honest support by other Arab countries. They had to do this themselves.” The Iron Fist policy of collective punishment, introduced by Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin on August 4, 1985, used home demolitions, administrative detention, and disproportionate force.

Hammam, Khalil, and Hussam were born after the Six-Day War and have known nothing but Israeli occupation. Their stories include triumph and tragedy within the context of a reality in Gaza marked by limited job opportunities, restricted movement, violence, and surveillance. Barber emphasizes the younger generation’s extensive involvement to illustrate the impact of that period, when twenty-five percent of young Palestinian men were detained or imprisoned.

I spoke with Barber about his efforts to bring the story of Gaza to the public. “No one else has taken readers to the micro level for three decades,” he told me. He chose his subjects in 2014 based on accessibility, their varied “personalities and approach to resisting the occupation,” and their ease with English. He then transformed the interviews into “narrative prose.” Barber also had access to women and children in culturally appropriate settings, which rounded out his portrayal.

Barber has written: “The publicity almost always stereotypes Gaza as a pathetic and vile place and its people as angry and vengeful. It is not and they are not.”

Our conversation also included the role of Egypt in the Gaza blockade; calls to Palestinian homes from Israeli commanders warning of imminent bombings (“Israel knows every detail of Gazan life,” Barber said); and Israel’s support of Hamas to ensure that there would be no negotiating partner.

Barber’s portrayals are: Hammam, The Social Man; Khalil, The Defender of Human Rights; and Hussam, The Educator. Each reveals a personal evolution over four to five decades. Their stories can be seen as a microcosm of others.

Hammam:

Hammam’s father, Fuad, was imprisoned in “unlimited detention” before he was born. (Since the occupation began, 800,000 Palestinians have been “detained.”) Although Hammam made a concerted effort to avoid disruptive activities, at 14 he was falsely accused of setting a tire on fire. A trip to a police station and a military headquarters in Khan Younis City followed. There, he was physically abused by male soldiers and a female officer.

Hammam decided to become a teacher. By 25, his marriage had been arranged, and his future wife had committed to completing her Bachelor’s Degree before they started a family. Hammam received a job offer with an international relief agency, where he remained for a year before becoming a researcher for a top Gazan civil society human rights organization.

Palestinian elections were held in January 2006. Barber explains the split between the Fatah president and the Hamas legislature. The ensuing civil war between the two led to the November 2008 blockade of Gaza. The internecine conflict between Hamas and Fatah would be disruptive to Palestinian lives, along with the blockade, which severely curtailed the supply of basic daily needs.

Hammam received his Master’s Degree in 2010 and now had three children. It was a year sandwiched between the December 2008 Israeli Operation Cast Lead and the 2012 Operation Pillar of Defense. In 2014, Israel instituted Operation Protective Edge, which saw fifty-one days of 6,000 airstrikes. Twenty-eight percent of the Gazan population (500,000 people) were displaced, 18,000 homes were decimated, and 2,200 Gazans were killed.

By 2017, at 42, Hammam was a headmaster at his school and a highly respected member of the community. He served as a mukhtar, a village leader looked to by others for guidance. It was the same year that the Palestinian Authority reduced his salary by forty-five percent. He considered relocating his family to Egypt but decided against it.

Three years later, at 45, Hammam had navigated the dilemma of splitting up his family, earned a PhD in educational leadership, and had weathered the COVID pandemic. Finances had dwindled, and periods of bombing barrages occurred. His one personal high note was the national recognition he received for his research “on the issue of Palestinian refugees at the level of the homeland and the diaspora.”

Khalil:

Khalil’s story begins at age 6 in the Khan Younis refugee camp near Gush Katif, sixteen Jewish settlements within the Gaza Strip protected by an electric fence. By 1987, when he was 17, Khalil saw confrontations with Israeli soldiers begin to escalate. That December, he was present on the first day of mass protests, but decided that engaging with the IDF was not the best path forward.

A key incident in Khalil’s history occurred in 1988. Caught in a street action over alleged stone throwing, Khalil’s ID card was confiscated and not returned. This left him undocumented. An identity card, issued by the Israeli Security Agency (ISA), was required for all Palestinians aged 16 and older. Without possession, a Palestinian risked detention or imprisonment. That night, soldiers came to his home and ordered Khalil and his older brother to remove debris and paint over graffiti from the day’s skirmishes. Afterwards, when asked for his ID, Khalil explained that his card had been taken that morning. He was arrested.

Blindfolded and zip-tied, Khalil and others were taken to an Israeli military compound. After several days, they were transferred to Ansar II, a prison in Gaza City, where they were required to stand outside, blindfolded, for one night and the following twelve hours. When finally questioned, Khalil explained that soldiers had taken his ID card. The officer recorded his details and told him to leave. During a second incarceration, Khalil served three months in Ansar III in the Negev. It was in prison that he learned about politics and Palestinian history.

At 27, Khalil became director of Al-Dameer, a Gazan human rights organization. He worked there for sixteen years. Khalil spoke out about abuses under Israeli occupation, but also criticized the Palestinian Authority (which arrested him three times) and Hamas, which accused him of “creating trouble among citizens” and called him in for questioning.

By age 45, problems with Hamas had escalated because of Khalil’s refusal to be silent. Hamas presented various allegations. The top charge was embezzlement from his organization. The stress led to illness requiring medication. His family decided he needed to leave Gaza, so Khalil spent six months recovering with relatives in Jordan. On returning to Gaza, Al-Dameer hired an independent team to review financial records. Khalil was cleared of wrongdoing and received his full severance pay.

At 52, Khalil decided to pursue other endeavors to earn sufficient income to assist his children with their education. One received a law degree, another entered telecommunications, and the third pursued computer engineering.

Hussam:

In 1986, Hussam was 13. He had spent years absorbing his grandmother’s stories about the Nakba. She told him of the military offensives in 1948 and the march to Gaza from the south with 250,000 other people. Settling in the al-Nuseirat refugee camp, the family restarted their lives. Wanting to learn more, Hussam went to the public library in Gaza to expand his knowledge. Information had been banned in Gaza since 1967. The word Palestine (or variations) was not allowed in school books, nor were any maps referencing the original territory.

To share his discoveries with his classmates, Hussam made a poster about “Palestine Across the Ages” to display on the wall. It was welcomed with interest by his peers, but the head Arabic teacher told him to take it down. “Don’t you know the soldiers could send me to prison for allowing such a thing in my classroom?” he said.

A year after the Intifada began, Hussamjoined a group in the camp. He became a leader in organizing demonstrations on Nakba Day and Land Day. Gatherings were held secretly as Israeli military law deemed group meetings illegal. His family understood his desire to be involved in the resistance to the occupation, but they insisted his obligation to his education was equally important. Regarding potential arrest, his father gave a major imperative: “Never implicate another.”

In 1989, when Hussam was 16, soldiers came to his family’s house in the middle of the night to arrest him and bring him to the Khan Younis military complex. On his twelfth day there, he was grilled on his activities. When he refused to give the names of others, he was beaten with wooden batons for several hours. His release came six days later, although sixty days after he was convicted of throwing stones based on the testimony of an IDF soldier. He was fined and sentenced to nine months at the Answar III prison in the Negev. This time period would cancel out his junior year in high school.

Upon his release, without an ID and with a prison record, Hussam focused on completing his education so he could attend university. From 18 to 21, Hussam worked on an undergraduate degree in English at Al-Azhar University in Gaza City. It was also a period of disillusionment for him. He believed that the Oslo Declaration was a “betrayal and an insult,” with specific disregard for those who had fought for a Palestinian state during the Intifada. Hussam was denied an overseas scholarship for graduate studies because he wasn’t a member of Fatah. He was demoralized by the actions of Palestinian political leaders, as he became acutely aware of the corruption and “cronyism” within all factions.

Hussam moved on to his first job, a teacher at the Palestinian Technical College, and at 22, he became engaged. Four years later, he was accepted at Brigham Young University to pursue a Master’s degree. Students sought him out for information on Islam, as well as the situation in Israel-Palestine. During this period, Hussam delved into the roots, ethics, and doctrines of his religion. It was to ground him in a way that the vagaries of politics had not.

When Hussam returned to Gaza after a year abroad, he married his fiancée immediately. During the following decade, he had five children, and within six years, he rose to the office of vice dean for academic affairs. Like Khalil and Hussam, everyday life was impacted by the Israeli blockade, higher food expenses, and sporadic electricity.

In 2010, Hussam went for his PhD in educational leadership. He received an offer from a university in Malaysia, a Muslim country, which was perfect for his family. He completed his dissertation in 2014, when he was 41.

That same year, an Israeli officer called the family’s landline at 5 a.m. to inform his father: “Your house is scheduled to be bombed in ten minutes.” With four levels above ground, each housing a different brother’s family, they faced an agonizing choice: stay or leave. Were these calls a strategy of intimidation or an actual attempt to alert and save people? Either way, the result was paralyzing.

In 2017, Hussam was a full professor at a government college. Like Hammam and 70,000 other PA workers in Gaza, his salary (and his wife’s) was cut in half. He saw his earnings decline due to the ongoing discord between the PA and Hamas, and he vigorously faulted both. By 2018, over half of Gaza’s working force was unemployed. Hussam began exploring the possibility of leaving the Strip. Instead, at the age of 46, Hussam committed to remaining in Gaza. He bought property near his in-laws’ house to build a home. The land was also next to an ongoing target of bombing by the Israelis—a power plant.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The second part of Barber’s book is devoted to WhatsApp messages he had with Hammam, Khalil, and Hussam over the one-year period after the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023. In his introduction to this material, Barber relates the details of Hamas assault, the reaction of Israeli military leaders, statistics on deaths (both Israeli soldiers and Palestinians in Gaza), and destruction (housing units, rubble and debris, cultural heritage). His footnotes are extensive.

Barber expressed his view of the importance of the material to me in his comment, “There’s so much value and richness [in the correspondence]. I postponed publication to include them, a live reportage [of what it is like] to live under attack.

With Barber’s permission, the following are brief excerpts from each man’s messages. After getting to know them and their lives through their preceding profiles, their words are even more resonant.

Hamman:

“Brian, the situation is terrifying. We are dying a slow death. Oh my God, what’s going on?…We may not meet again after today. We may all die at any time, my friend…No electricity at all for 27 days. Darkness is deadly…First time I am crying with sorrow. We have nothing. We are waiting. We are dying every day. Everything is destroyed. Khan Younis is destroyed…Life has become unbearable…Still waiting for a ceasefire…I have become unable to think. I don’t know where these idiots will take us.”

Khalil:

“Hi Brian, so far we are good. Hopefully we will be safe. The war has started to be more aggressive. It seems that they decide to invade…We are not good but we are strong enough…I am still waiting for an end of this foolishness…The news about Rafah is not good. They may invade Rafah soon…It is a real nightmare…The news focuses on the hostages and ignores the innocents who were victims for both Israel and Hamas…Nobody can imagine the stories of killings everywhere in Gaza…No one can know if s/he will survive this genocide. We live until when? Who will be next?…Death is the only certainty for the Palestinians in Gaza.”

Hussam:

“I am fine, but still stuck in Egypt…Currently, I am back to Gaza. They opened the borders during the ceasefire for a few days, and I barely managed to cross…I hope this war ends soon…Once again, forced to be displaced, along with all the extended family. I am in Rafah right now!…Nobody can imagine what will happen after this genocide ends. Generally, a nonstop misery and suffering is awaiting Palestinians trying to restore their lives…The psychological and the social consequences of this horrific genocide will be catastrophic to Palestinians and the world alike…The situation is so terrifying in my neighborhood…Tomorrow, we will be resuming our search for the people under the rubble…The situation in Gaza is way beyond human capacity to bear…I earnestly pray to God to bring a swift end to this genocide.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Barber hopes the book will help an audience understand the accomplishments and challenges of Palestinians in Gaza. “My biggest concern,” Barber underscored, “is that enough people don’t understand what’s happening on the ground.” He pointed to the “depersonalization of Gazans” in media reports.

Perhaps the statement that best captures that sentiment is the one conveyed as early as page 4. Barber tells of his trip to various schools throughout the Strip in 1995 to meet students. A young man implores him:

“Please go home and tell the world that we are not all terrorists.”

Cover Photo: Brian K. Barber

Gaza map: Created by Khaled Alostath

Courtesy of Brian K. Barber