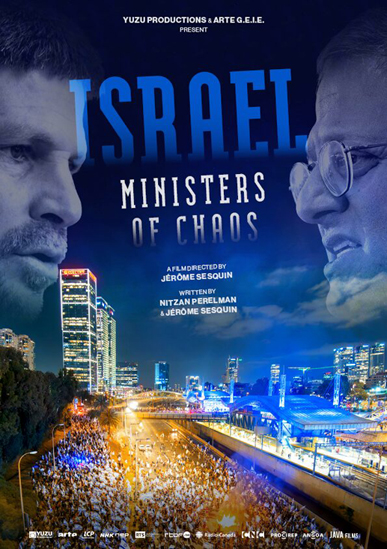

“Israel: Ministers of Chaos”

Many American Jews are presently focused on concerns of antisemitism in the United States. In New York City, the ADL launched a “monitor” to track the Mamdani administration to parse out actions and words that could be considered threatening to Jewish residents. A top concern is “anti-Zionism.” Yet, many Jews in the United States are not aware of the severe threat of fascist forces and ideology in Israel.

“Ministers of Chaos,” shown at the Other Israel Film Festival in Manhattan, takes a deep look at the tentacles of racism and ethnonationalism in today’s state of Israel. Directed by Jérôme Sesquin and co-written with Nitzan Perelman, the documentary begins with ominous music, a precursor of the narrative to come.

Although these two men were not new to me, I found the 58-minute film extremely disquieting. The profiles of Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, false prophets of the 21st century, are a wake-up call to all those who believe that Israel is on the right track.

The opening sequence takes place only a few months into the Gaza war, when a conference was held in Jerusalem in January 2024. The attendees, about 5,000 in number, were primarily settlers from the West Bank. On stage were government officials, including the Minister of National Security, Ben-Gvir, and the Minister of Finance, and a Defense Ministry delegate, Smotrich.

The event was dedicated to the “recolonization of Gaza.” Two decades after Israel left that land, the statements being presented from the podium were that without settlements on the ground, there “would be no security inside Israel.” To rousing cheers, Smotrich delivered the statement, “With God’s help, the eternal people will win.”

Ben-Gvir presented his agenda with a different tone. “We must encourage them [the Palestinians] to leave,” he said. Extracting a phrase from the Torah, he invoked, “You will conquer the land and settle there.” He added matter-of-factly, “It’s always been ours.” He led those assembled in a chant of “Death to the terrorists.” (And no, they were not referencing themselves.)

The question posed by the film is, “How did these far-right religious operatives get into power?” The short answer is: Benjamin Netanyahu, who joined an alliance with them so he could secure his Prime Ministership. In December 2022, Netanyahu returned to power with Likud and several far-right parties. Smotrich is the head of the Religious Zionist party, and Ben-Gvir heads the supremacist Jewish Power party.

When this coalition announced plans for “judicial reform,” it ignited major national turmoil. Such a move would include a takeover of the Israeli Supreme Court, legal advisers, and the Attorney General. The perpetrators considered this initiative “just the first step.” As the film explains, progressive Israeli citizens saw the move as a “coup d’etat” because in Israel’s parliamentary democracy, the Supreme Court serves as a counterbalance to the executive branch and the Knesset. There was also the continuous sidebar of Netanyahu’s extensive legal problems.

Shikma Bressler, a physicist and leader in the protest movement, is interviewed. She maintains that if Israel is to remain a democracy, it needs to reject dictatorship. Bressler described Ben-Gvir and Smotrich as leaders of a “racist and fascist movement,” who believe themselves to be “superior to less religious Jews and non-Jews.” She connected their mission to take over the “Biblical land of Israel” with their supremacist agenda to rule over the “Arab and Palestinian population.”

Israeli society is deeply fractured (much like America), and the split puts the religious settlers in the camp that supports Ben-Gvir and Smotrich. They want an annexation of the Occupied Territories and see the Supreme Court as an obstacle to their vision of a “greater Israel.” Smotrich specifically leans on his particular interpretation of “The words of God.”

Backstory on Smotrich is provided by journalist Ruth Margalit, who has researched him extensively. The son of an Orthodox rabbi, Smotrich grew up in the Beit El settlement in the West Bank, immersed in the settler movement’s philosophy. His entry into the public sphere began in 2017, with a series of videos presenting himself to Israeli society after he was first elected to parliament. He agitates with potential options for the extension of Israeli sovereignty “to the whole of the West Bank.” Smotrich’s views are laced with condescension and sarcasm. He states, “They can give up their Palestinian national aspirations and get resident status, but no rights to vote.” His secondary alternative is for Palestinians to leave for another country, which he notes the state will help to facilitate. He comments with a smirk, “I’m very good at packing porcelain and hookahs.” Margalit emphasizes, “Before Netanyahu, he is one of the original drafters of these ideas.”

An interview with Smotrich shows him discussing how he wants a state governed according to the “Jewish people’s values.” When asked about territorial boundaries, he responds with a smile and an answer he ascribes to previous great religious scholars, “The fate of Jerusalem is to extend as far as Damascus.”

That is considered a maximalist and radical view, but for how long?

The origins of this mindset and movement are located in the aftermath of the 1967 war. A “nationalist and religious movement” evolved as Israel captured terrain that tripled the size of the country. The victory was interpreted as “a prophecy.” Ami Pedahzur, an Israeli professor and author of “The Triumph of Israel’s Radical Right” (2012), is on hand to discuss how the acquisition of these territories made it feasible to put this ideology into play.

Pedahzur references the writings of Rabbi Abraham Issac Kook and his belief that Jews must “settle in all the land promised to them by God in the Old Testament.” This point of view contributed to the rise of the Gush Emunim (Block of Faithful) movement.

A segment is centered on the Elon Moreh settlement, sited on Palestinian land. Jews believe Abraham built an altar after God appeared to him and said, “To your offspring I will give this land.” (Genesis 12:7) To demonstrate the role of the Labor government in settlement history and why settlers felt that they were betrayed, Sesquin recounts the story in which Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, in an effort to appease the settlers, sent Shimon Peres to make a deal which would allow settlement in Elon Moreh in “Samaria.” This opened the way to what is now 500,000 Israelis living in settlements. The West Bank soon became subject to ongoing Israeli confiscations of land for military use, agricultural sites, and infrastructure erected to exclusively benefit Jewish Israelis.

Ben-Gvir has been part of the far right for three decades. He presents as an agent provocateur. The video clip of him vandalizing Rabin’s car is well-known, as is his statement remarking that if Rabin’s vehicle is accessible, “then we can reach Rabin.” Ben-Gvir was 19 years old in 1995 when Rabin was murdered.

Pedahzur gives a primer on Meir Kahane, known to American Jews as the founder of the Jewish Defense League. Arrested in the United States by the FBI, Kahane moved to Israel in 1971 and founded the Kach political party. Their platform is constructed around the expulsion of all Arab [Palestinian] citizens from Israel. When Kahane won a seat in the Knesset in 1984, he was shunned by other members, who would leave the floor when he spoke. Four years later, Israel’s Supreme Court banned the Kach Party for inciting racism. In 1990, Kahane was shot and killed while speaking in New York City. Pedahzur explains that Kahane’s followers came “from the periphery” and posited that his ideas were connected to the “populist, radical right in Europe.” Margalit offers that most of the Kahanist recruits originally came from “at-risk youths,” including those who had dropped out of high school.

To illustrate this point, Gilad Sade, a former Ben-Gvir follower, is interviewed. He was raised as a Kahanist and speaks about his actions as a teenager, including destroying Palestinian property and other acts of vandalism during the Second Intifada. He states, “I was a kid. I had no idea what I was doing. I could have been killed.”

In 2005, Ariel Sharon withdrew twenty-one settlements from Gaza, leaving religious nationalists feeling deceived. Smotrich, then 24 years old, was arrested along with others by the Shin Bet. He was held and questioned for three weeks and then sent home. Smotrich frequently uses what he considers the governmental 2005 duplicity to incite his followers.

Referencing Ben-Gvir’s public reach, Amal Oraby, Palestinian writer, lawyer, and citizen of Israel, attributes Ben-Gvir’s “rock star” status to the Israeli media. By giving so much coverage to Ben-Gvir’s objectives, it has led the way to “normalizing racism and Jewish supremacy.”

When the Nation-State Law was passed in 2018, Hebrew was designated the “official” language of Israel. The legislation also codified that “only Jews have a right to self-determination.” The ideology of the “nationalist right” became woven into the fabric of the state.

Forty-five minutes into the film, the October 7 attack is introduced. A new “unity government” is proposed, configured on dropping Ben Gvir and Smotrich from the coalition. Netanyahu declines.

In early 2024, Smotrich used the deflection of the war in Gaza to announce the construction of 3500 new housing units and the expropriation of 800 nectares (1,977 acres) belonging to Palestinians. In essence, Smotrich has built his own infrastructure in the West Bank. He is putting into play his “Decisive Plan.” Coming from a country that was built with survivors of the Final Solution, the concept is painfully ironic.

I reached out to director Jérôme Sesquin, based in Paris, for insights into the documentary. It was made for the French public television station and aired 18 months ago. Sesquin’s premise was to delve into the radical religious right movement in Israel.

Sesquin told me that he has relatives in Israel and in the United States. His family was originally from Poland and Lithuania, and came to France in the 1920s and 1930s. Other members left for Israel in the 1950s. He explained that his familial connections spanned the political spectrum in Israel, from left to radical right, and that he spoke with all of them while shaping the film. He was in the middle of editing when October 7 occurred.

“This government is very particular,” Sequin said. “It’s why the war lasted so long. Netanyahu doesn’t want to lose power, so he needed a coalition to not stop the war.”

The documentary concludes with the statement that these two “evil geniuses” will do everything to oppose the end of the Occupation and a fair peace agreement with the Palestinians.

Given the scope of their current governmental portfolios and influence, it remains undetermined how far they will get.

Images: Courtesy of Seventh Art Releasing