Rabbi Arik Ascherman: Human Rights as a Jewish Religious Obligation

In the days of the Old Testament, iconoclastic prophets were not always appreciated or heeded by the Israelites. Frequently, they were seen as nettlesome presences giving voice to truths that the populace was reluctant to confront.

Rabbi Arik Ascherman fits the bill, down to the physical look. With a white beard and an elongated build, he could easily be envisioned in a garment of rough cloth with feet shod in sandals.

When I met him on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in December, at a private home hosting a “parlor meeting,” Ascherman was simply dressed in a button-down blue shirt and dark pants. He had the look of an ascetic but was warm and open, especially given that in less than an hour he would be addressing a roomful of people.

I had heard Ascherman speak numerous times on Zooms, always with passion and emotion, about the work he is doing with Torat Tzedek (Torah of Justice), an organization he founded in 2017 and for which he serves as Executive Director.

His trip to the United States had a three-part agenda. He wanted to bring the story of how the human rights of Palestinians in the West Bank were being physically violated; to talk about his experiences in trying to stop the abuses; and to recruit more Americans to travel to Israel-Palestine for on-the-ground “protective presence” action. As with any non-profit, requests for financial support were part of the equation, especially given the extensive expenses of the struggle.

I was interested in digging into Ascherman’s backstory and ideas, and in how he arrived at where he is today. I also wanted to speak to him in his capacity as a Rabbi, to ask questions that were crushing me about the ongoing use of torture by Israelis against Palestinians.

Ascherman related that he knew he wanted to be a Rabbi by age six (fireman and paleontologist lost out). By the time he approached his Bar Mitzvah, Ascherman was heavily imprinted and “enamored” with the ethical values he believed Judaism had to offer. He didn’t necessarily see himself living in Israel, nor did he believe that all Jews had to.

During our conversation, Ascherman prefaced numerous statements with “The God I believe in…” or “The way I understand Torah…,” setting them up as a precursor to his concept of “faith-based” human rights activism. The key to his philosophy and the starting point for his efforts is the deeply held belief that every person is made in God’s image and that their human rights have to be protected.

Acknowledging what Ascherman termed “a dichotomy in the Bible,” he referenced the kinds of texts he focuses on, rather than the interpretations advocated by followers of Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich. Ascherman added, “Our religion is based in debate.”

Posing the question, “Why bother fighting for Judaism?” Ascherman observed that in the state of Israel, his views of the Bible were “in the minority.” He emphasized, “But if you’re a person of faith, it’s not something you can turn off and on like a light bulb. Our fight is to show that our Judaism is equally valid. We can’t abandon the field. We have to fight for the soul of our people and our religion, for what we believe in, and to convince more people that this is the Judaism we should follow. Our tradition is too multilayered and complex for (the assertion), ‘Judaism says…’ ”

Ascherman discussed Arthur Hertzberg, who called for the establishment of a Palestinian state in 1967, the Jewish socialist pioneers who thought they could unite the Jewish and Arab proletariat, and Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s concepts of Zionism.

We traced Ascherman’s trajectory, beginning with his not being admitted to the Hebrew Union College because they wanted him to gain more experience in the “outside world.” In response, Ascherman connected to the Interns for Peace program, which builds Arab-Israeli relationships. He began to see Israel as a place where he could do Tikkun Olam and make a contribution. Ascherman was ordained in 1989 and established residence in Israel in 1994. He began his leadership role at Rabbis for Human Rights North America (1995-2016).

Torat Tzedek has had other concerns on its radar, all of which reflect a push back against Israeli state injustices and inequalities. They have included rights for asylum seekers from Africa, legal petitions to the Israeli High Court, public housing support, setting up human rights Yeshivas, fighting the evictions of Palestinians from their homes in East Jerusalem, actions to stop home demolitions, and protections for Israeli Bedouin residents of the Negev.

For Ascherman, the whole picture evolves from the Genesis quote (Chapter 1, Verse 27), that every individual is made in God’s image. Therefore, each person’s human rights must be protected. At this juncture, I asked him about the ongoing torture of Palestinians by Israelis. Ascherman’s response to me was the following: “Jews see themselves as the most oppressed people, which has left scars on their souls and anger.” Ascherman believes that the motivation for those “bad Jews” comes from a “xenophobic understanding of Judaism,” an “us against the world” mentality. In essence, he saw that this system of interpretation leads some Jews to a belief that “our past suffering privileges us.”

By way of explanation, Ascherman launched into a story about Menachem Begin. “Do you know what his first act as Prime Minister was?” he asked me. “It was to bring Vietnamese boat people to Israel.” He paused and followed up with, “But he also pushed the settlement movement. Begin believed that the world that didn’t lift a finger to save Jews had no right to tell us what to do.”

We discussed the two schools of thought bequeathed to the Jews from the Holocaust. The first is that the legacy of the Holocaust gives Jews a specific responsibility to speak out on behalf of others who are being oppressed and maltreated, versus those who believe that the “world owes us. We’re looking out for ourselves, and that’s it.” Ascherman told me that he believes “Israelis see themselves as oppressed,” which leads to their logic that “our survival comes first.”

Ascherman brought several Jewish thinkers into the discussion. He mentioned Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, who had been prescient in his belief that having a state and the power that came with it could lead to internal conflicts, a shift toward an emphasis on state power, and a transformation away from Judaism’s spiritual aspects. Ascherman injected, “The Torah warned us not to behave as Egyptians, where might makes right.” It was hard not to think of Netanyahu’s speech, calling for Israel to become the “super Sparta of the Middle East.”

It was the 1967 war, Ascherman maintained, when Israel feared for its survival, which resulted in “messianic passions [being] released.” Ascherman invoked the beliefs of Yeshayahu Leibowitz, who advocated for the return of militarily conquered lands based on “moral reasons.” Leibowitz stated early on, “The Occupation is corrupting.” Yet, for other Jews, when “biblical lands” ended up in Israeli hands after the Six-Day War, they saw it as an “act of God,” commanding them to “settle and redeem the land.”

As people began arriving, I posed a final question. “Do you think Israel is going to self-destruct?”

“It could,” he responded. “It is very scary, this messianic fervor that has captured so many Israelis. I’ve spent most of my career fighting against occupation. Any concept of a new order in the Middle East has to include justice for the Palestinians. We are violating the human rights of other people.”

* * * *

A group of around thirty-five people had seated themselves in the living room. Those present skewed older, but several were in their twenties, including a young woman I spoke to who was considering traveling to the West Bank.

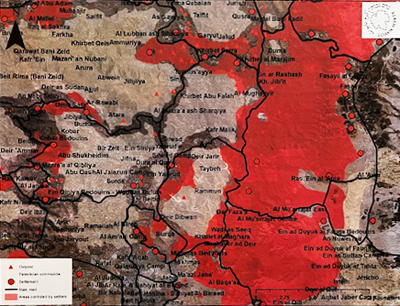

The host, Paul, introduced Ascherman. There was a simultaneous Zoom of the event underway, and a map projected on a screen, where a nine-minute video, “A Protective Presence,” was shown. The land illustration documented areas where the Palestinian communities were, overlapped by outposts, settlements, and complete zones controlled by settlers.

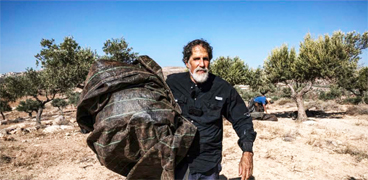

Photo: Courtesy of Torat Tzedek

“Rabbi Arik is praying with his body,” Paul said. “On a daily basis, he confronts messianic settlers. He is a deep believer in tradition. We are at a crossroads of history. Where will our people stand?”

Ascherman began to describe his engagement, which ranges from legal advocacy (helping a Palestinian landowner to file a complaint) to acting as a physical barrier between Palestinians and radical, often violent, settlers. “We have a finger in the dyke, but the dyke is disintegrating,” he said.

Laying out the strategy of the settlers, Ascherman elucidated how they established shepherding outposts to take over and displace Palestinians from their lands. They bring in flocks with the mindset of, “If we can’t expel them from the West Bank, we’ll push them out of Area C to Areas A and B.”

Although Ascherman has had successes, such as stopping the construction of a settler-built road, his tribulations have been extensive. He has been beaten, put in jail with no sustenance but water (“It was to get me out of the way!”), seen pogroms enacted upon Palestinian villages, and the cutting down of olive trees with chainsaws. “[Palestinian] communities are fleeing, sometimes at gunpoint,” he stated. “Judges in the Israeli high court don’t believe that the police can’t do the job.”

Photo: Marcia G. Yerman

In a lengthy (11/20/25) Times of Israel blog, Ascherman wrote a piece specifically directed to Israel’s President Herzog, refuting that the assaults upon Palestinians are only perpetrated by a small handful of “troubled youth.” Rather, as he told those gathered, “We have to accept the reality. It’s not just a handful of youth. We have photos of soldiers working hand in hand with settlers.”

When speaking about the complicity of Israeli security forces, Ascherman commented that some of the most violent days are Shabbat. He painted a picture of a “horde of settlers on the ridge,” Palestinian homes in flames, sheep stolen, and a volunteer with a broken arm.

After setting the stage, Ascherman delivered his “ask.” It went beyond money, though they need that too in order to defray the cost of legal battles, and in one instance, 25,000 shekels to rebuild after an attack in October 2025. Ascherman was upfront when he said, “But tonight, I need more than that. I need your feet on the ground. There aren’t enough of us Israelis. We need you with us. If we had twenty people 24/7, it would be a game-changer. This is the reality we are facing right now.”

Pointing to the map, Ascherman said, “All the red is under settler control. Palestinians are still in their homes due to incredible bravery, but settlers are going after villages now.” He pinpointed his commitment to Palestinian villagers. “We have to try everything, because everything is on the line. If there is anything that can redeem what we’ve done…” His voice trailed off.

Ascherman continued. “One thing I can promise [to Palestinians], you will not be alone.” His voice broke. “Like when our doors were broken down. You will not be alone. We will do whatever, whatever, whatever we can.”

It was a highly emotional moment, and the room was completely silent.

Then, it was time for questions. Several were about American national policy. Ascherman believes in pushing for support and activation of the Leahy law, which prohibits American arms sales when they are used in human rights violations. Ascherman underscored, “It’s for all countries. It’s not singling Israel out. It’s holding it accountable.”

Margaret Olin, who was sitting next to me, rose to share her experiences in the West Bank. Olin is a photographer and a historian of visual culture. She spoke of going with Ascherman on his missions to the Jordan Valley several times. Later, she related to me, “Ascherman’s pure tirelessness impressed me no end. As I got to know him increasingly better, I found him always ready to do anything to help the cause. I do not know if I have ever met anyone as dedicated as Arik.”

Before closing out the evening, Ascherman quoted Rabbi David Saperstein, who said, “There have been times when people have to take risks, and this is one of those times.”